Digest of Fluent Python: Part IV - Object-Oriented Idioms (decorators, closure, references, mutability, recycling, pythonic 实践, inheritance)

Chapter 7 - Function Decorators and Closures

7.1 Decorators 101

A decorator is a callable which can take the decorated function as argument. (另外还有 class decorator)

Assume we have a decorator named foo,

@foo

def baz():

print('running baz')

# ----- is roughly equivalent to -----

def foo(func):

print('running foo')

return func

def baz():

print('running baz')

baz = foo(baz)

注意上面的例子中:

baz定义结束时,@foo会立即执行 (相当于替换了baz的定义)- 换言之,当

baz所在的 module 被 load 进来的时候,@foo就会执行

- 换言之,当

- 调用

baz()时并不会执行@foo

7.2 When Python Executes Decorators

A key feature of decorators is that they run right after the decorated function is defined. That is usually at import time.

Decorated functions are invoked at runtime of course.

7.3 Decorator-Enhanced Strategy Pattern

promos = [] # promotions registry

def promotion(promo_func):

promos.append(promo_func) # register this promotion

return promo_func

@promotion

def fidelity(order):

"""5% discount for customers with 1000 or more fidelity points"""

...

@promotion

def bulk_item(order):

"""10% discount for each LineItem with 20 or more units"""

...

@promotion

def large_order(order):

"""7% discount for orders with 10 or more distinct items"""

...

def best_promo(order):

"""Select best discount available"""

return max(promo(order) for promo in promos)

Pros:

- The promotion strategy functions don’t have to use special names.

- The

@promotiondecorator highlights the purpose of the decorated function, and also makes it easy to temporarily disable a promotion - Promotional discount strategies may be defined in other modules, anywhere in the system, as long as the

@promotiondecorator is applied to them.

7.4 Variable Scope Rules

Code that uses inner functions almost always depends on closures to operate correctly. To understand closures, we need to take a step back a have a close look at how variable scopes work in Python.

>>> b = 6

>>> def f2(a):

... print(a)

... print(b)

... b = 9

...

>>> f2(3)

3

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 3, in f2

UnboundLocalError: local variable 'b' referenced before assignment

The fact is, when Python compiles the body of the function, it decides that b is a local variable because it is assigned within the function. The generated bytecode reflects this decision and will try to fetch b from the local environment.

Try the following code to see bytecode:

>>> from dis import dis

>>> dis(f2)

1 0 RESUME 0

2 2 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (NULL + print)

12 LOAD_FAST 0 (a)

14 CALL 1

22 POP_TOP

3 24 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (NULL + print)

34 LOAD_FAST_CHECK 1 (b)

36 CALL 1

44 POP_TOP

4 46 LOAD_CONST 1 (9)

48 STORE_FAST 1 (b)

50 RETURN_CONST 0 (None)

This is not a bug, but a design choice: Python does not require you to declare variables, but assumes that a variable assigned in the body of a function is local.

If we want the interpreter to treat b as a global variable in spite of the assignment within the function, we use the global declaration:

>>> b = 6

>>> def f2(a):

... global b

... print(a)

... print(b)

... b = 9

...

>>> f2(3)

3

6

>>> b

9

>>> dis(f2)

1 0 RESUME 0

3 2 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (NULL + print)

12 LOAD_FAST 0 (a)

14 CALL 1

22 POP_TOP

4 24 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (NULL + print)

34 LOAD_GLOBAL 2 (b)

44 CALL 1

52 POP_TOP

5 54 LOAD_CONST 1 (9)

56 STORE_GLOBAL 1 (b)

58 RETURN_CONST 0 (None)

7.5 Closures

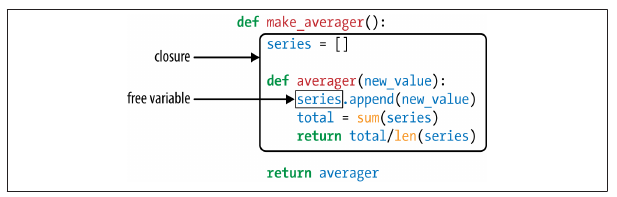

A closure is a function with an extended scope that encompasses nonglobal variables referenced in the body of the function but not defined there. It does not matter whether the function is anonymous or not; what matters is that it can access nonglobal variables that are defined outside of its body.

Consider the following example:

>>> avg = make_averager()

>>> avg(10)

10.0

>>> avg(11)

10.5

>>> avg(12)

11.0

Within averager, series is a free variable. This is a technical term meaning a variable that is not bound in the local scope. 我们也称 The closure for averager extends the scope of that function to include the binding for the free variable series.

Inspecting the free variable:

>>> avg.__code__.co_varnames

('new_value', 'total')

>>> avg.__code__.co_freevars

('series',)

The binding for series is kept in the __closure__ attribute of the returned function avg. Each item in avg.__closure__ corresponds to a name in avg.__code__.co_freevars. These items are “cells”, and they have an attribute called cell_contents where the actual value can be found.

>>> avg.__code__.co_freevars

('series',)

>>> avg.__closure__

(<cell at 0x107a44f78: list object at 0x107a91a48>,)

>>> avg.__closure__[0].cell_contents

[10, 11, 12]

7.6 The nonlocal Declaration

之前的 make_averager 实现不够 efficient,一个新的写法是:

# Wrong!

def make_averager():

count = 0

total = 0

def averager(new_value):

count += 1

total += new_value

return total / count

return averager

但是运行时出错:

>>> avg = make_averager()

>>> avg(10)

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

UnboundLocalError: local variable 'count' referenced before assignment

原因是:

- 在 closure 范围内,nested function body 内部对 free variable

foo的 “rebind” 操作,都会 implicitly create local variblefoo- 之前的

series.append(new_value)操作不会触发 “创建 local varibleseries” 是因为:list是 mutable 的list.append()的操作不会创建新的list

- 而这里

count += 1和total += new_value的操作会创建两个 local variablecount和total是因为:- number 是 immutable 的

+=操作会创建新的 number

- 之前的

- 隐式创建的 local variable 会干扰你对 free varible 的引用 (编译器不知道你要用的具体是哪一个)

解决这个问题的方法是:用 nonlocal 声明。It lets you flag a variable as a free variable even when it is assigned a new value within the function.

# OK!

def make_averager():

count = 0

total = 0

def averager(new_value):

nonlocal count, total # key statement!

count += 1

total += new_value

return total / count

return averager

7.7 Decorators in the Standard Library

7.7.1 Memoization with functools.lru_cache

注意 decorator 可以多包一层,以达到可以带参初始化的目的。

我们先看原始的写法:

# 原始 decorator

def foo(func):

print('running foo')

return func

@foo

def baz():

print('running baz')

相当于 baz = foo(baz)。

带参的写法:

# 带参 decorator

def foo(msg):

def wrapper(func):

print(msg)

return func

return wrapper

@foo('running foo another way')

def baz():

print('running baz')

相当于 baz = foo(msg)(baz)。

functools.lru_cache 就是一个带参 decorator,它的作用是 to cache recent call results。它内部会维护一个 dict 来记录 <arg_list, result>,从而达到 cache 的作用。适用的场景比如:

- http request

- 递归

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize=128)

def fibonacci(n):

if n < 2:

return n

return fibonacci(n-2) + fibonacci(n-1)

7.7.2 Generic Functions with Single Dispatch

这个厉害了。书上的例子是 “格式输出 html 代码”,针对不同的类型的变量,有不同的输出策略。不用 OO,用 function 就可以实现 overloading.

from functools import singledispatch

from collections import abc

import numbers

import html

@singledispatch

def htmlize(obj):

content = html.escape(repr(obj))

return '<pre>{}</pre>'.format(content)

@htmlize.register(str)

def _(text):

content = html.escape(text).replace('\n', '<br>\n')

return '<p>{0}</p>'.format(content)

@htmlize.register(numbers.Integral)

def _(n):

return '<pre>{0} (0x{0:x})</pre>'.format(n)

@htmlize.register(tuple)

@htmlize.register(abc.MutableSequence)

def _(seq):

inner = '</li>\n<li>'.join(htmlize(item) for item in seq)

return '<ul>\n<li>' + inner + '</li>\n</ul>'

- 带

@singledispatch标记的 function 我们称为 generic function.- 默认实现是

htmlize(obj) str类型的输入对应的实现是_(text)- 依此类推

- 默认实现是

- The name of the specialized functions is irrelevant;

_is a good choice to make this clear. - 可以映射多个输入类型到同一个 specialized function

需要注意的是:@singledispatch is not designed to bring Java-style method overloading to Python. The advantage of @singledispath is supporting modular extension: each module can register a specialized function for each type it supports.

7.8 Stacked Decorators

@d1

@d2

def foo():

pass

等同于 foo = d1(d2(foo)),注意顺序

Digress: @functools.wrap

decorator 有个小弊端是:decorated function 的 name 和 docstring 属性会跑到 wrapper function 那里去,比如:

def foo(func):

def func_wrapper(*args, **kwds):

"""This is foo.func_wrapper()"""

return func(*args, **kwds)

return func_wrapper

@foo

def baz():

"""This is baz()"""

>>> baz.__name__

'func_wrapper'

>>> baz.__doc__

'This is foo.func_wrapper()'

为了解决这个问题,我们可以用 @functools.wrap 来 decorate 这个 wrapper:

from functools import wraps

def foo(func):

@wraps(func)

def func_wrapper(*args, **kwds):

"""This is foo.func_wrapper()"""

return func(*args, **kwds)

return func_wrapper

@foo

def baz():

"""This is baz()"""

>>> baz.__name__

'baz'

>>> baz.__doc__

'This is baz()'

它的逻辑是:

wrap(func)返回一个functools.partial(functools.update_wrapper, wrapped=func)wrap(func)(func_wrapper)相当于func_wrapper = functools.update_wrapper(wrapper=func_wrapper, wrapped=func)

Chapter 8 - Object References, Mutability, and Recycling

We start the chapter by presenting a metaphor for variables in Python: variables are labels, not boxes.

8.1 Variables Are Not Boxes

Better to say: “Variable s is assigned to the seesaw,” but never “The seesaw is assigned to variable s.” With reference variables, it makes much more sense to say that the variable is assigned to an object, and not the other way around. After all, the object is created before the assignment.

To understand an assignment in Python, always read the righthand side first: that’s where the object is created or retrieved. After that, the variable on the left is bound to the object, like a label stuck to it. Just forget about the boxes.

8.2 Identity, Equality, and Aliases

Every object has

- an identity

- comparable using

is

- comparable using

- a type

- a value (the data it holds)

- comparable using

==(python 的foo == bar相当于 java 的foo.equals(bar))

- comparable using

An object’s identity never changes once it has been created; you may think of it as the object’s address in memory. The is operator compares the identity of two objects; the id() function returns an integer representing its identity.

The real meaning of an object’s ID is implementation-dependent. In CPython, id() returns the memory address of the object, but it may be something else in another Python interpreter. The key point is that the ID is guaranteed to be a unique numeric label, and it will never change during the life of the object.

In practice, we rarely use the id() function while programming. Identity checks are most often done with the is operator, and not by comparing IDs.

8.2.1 Choosing Between == and is

The == operator compares the values of objects, while is compares their identities.

However, if you are comparing a variable to a singleton, then it makes sense to use is. E.g. if x is None.

The is operator is faster than ==, because it cannot be overloaded, so Python does not have to find and invoke special methods to evaluate it, and computing is as simplecomparing two integer IDs. In contrast, a == b is syntactic sugar for a.__eq__(b). The __eq__ method inherited from object compares object IDs, so it produces the same result as is. But most built-in types override __eq__ with more meaningful implementations that actually take into account the values of the object attributes.

8.2.2 The Relative Immutability of Tuples

注意 immutable 的含义是本身的 value 不可变:

>>> a = (1,2)

>>> a[0] = 11

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

>>> b = "hello"

>>> b[0] = "w"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

你需要新的值就自己去创建一个新的,不可能把我当前的值修改一下再拿去用。

但是,Tuples, like most Python collections–lists, dicts, sets, etc.–hold references to objects. If the referenced items are mutable, they may change even if the tuple itself does not.

>>> t1 = (1, 2, [30, 40])

>>> id(t1[-1])

4302515784

>>> t1[-1].append(99)

>>> t1

(1, 2, [30, 40, 99])

>>> id(t1[-1])

4302515784

所以我们可以更新下 immutable 的定义:本身的 value 不可变;如果 value 内部包含 reference,这个 reference 不可变,但 reference 对应的 object 可变。

tuple 设计成 immutable 的好处是:

- python 中必须 immutable 才能 hashable,所以 tuple 可以做 dict 的 key (list 就不可以)

- function 接收参数 tuple 时不用担心 tuple 被篡改,可以免去 defensive copy 的操作,算得上是一种 optimization

8.3 Copies Are Shallow by Default

For mutable sequences, there are 2 ways of copying:

- By constructor:

a = [1,2]; b = list(a) - By slicing:

a = [1,2]; b = a[:]

N.B. for a tuple t, neither t[:] nor tuple(t) makes a copy, but returns a reference to the same object. The same behavior can be observed with instances of str, bytes, and frozenset.

但是!这样的 copy 都是 shallow copy。考虑 list 内还有 list 和 tuple 的场景:

a = [1, [22, 33, 44], (7, 8, 9)]

b = list(a)

a.append(100) # changes ONLY a

a[1].remove(44) # changes BOTH a and b

print('a:', a) # a: [1, [22, 33], (7, 8, 9), 100]

print('b:', b) # b: [1, [22, 33], (7, 8, 9)]

b[1] += [55, 66] # changes BOTH a and b

b[2] += (10, 11) # changes ONLY b because tuples are immutable

print('a:', a) # a: [1, [22, 33, 55, 66], (7, 8, 9), 100]

print('b:', b) # b: [1, [22, 33, 55, 66], (7, 8, 9, 10, 11)]

8.3.1 Deep and Shallow Copies of Arbitrary Objects

from copy import copy, deepcopy

a = [1, [22, 33, 44], (7, 8, 9)]

b = copy(a) # shallow copy

c = deepcopy(a) # as name sugguests

>>> id(a[1])

140001961723656

>>> id(b[1])

140001961723656

>>> id(c[1])

140001961723592

Note that making deep copies is not a simple matter in the general case.

- Objects may have cyclic references that would cause a naive algorithm to enter an infinite loop.

- The

deepcopyfunction remembers the objects already copied to handle cyclic references gracefully.

- The

- Also, a deep copy may be too deep in some cases. For example, objects may refer external resources or singletons that should not be copied.

- You can control the behavior of both

copyanddeepcopyby implementing the__copy__()and__deepcopy__()special methods

- You can control the behavior of both

8.4 Function Parameters as References

The only mode of parameter passing in Python is call by sharing. That is the same mode used in most OO languages, including Ruby, SmallTalk, and Java (this applies to Java reference types; primitive types use call by value). Call by sharing means that each formal parameter of the function gets a copy of each reference in the arguments. In other words, the parameters inside the function become aliases of the actual arguments.

The result of this scheme is that a function may change any mutable object passed as a parameter, but it cannot change the identity of those objects.

8.4.1 Mutable Types as Parameter Defaults: Bad Idea

这个现象前所未见!先上例子

class HauntedBus:

"""A bus model haunted by ghost passengers"""

def __init__(self, passengers=[]): # Tricky Here!

self.passengers = passengers

def pick(self, name):

self.passengers.append(name)

def drop(self, name):

self.passengers.remove(name)

>>> bus1 = HauntedBus()

>>> bus1.pick('Alice')

>>> bus2 = HauntedBus()

>>> bus2.passengers

['Alice']

>>> bus2.pick('Bob')

>>> bus1.passengers

['Alice', 'Bob']

The problem is that each default value is eval‐ uated when the function is defined–i.e., usually when the module is loaded–and the default values become attributes of the function object. So if a default value is a mutable object, and you change it, the change will affect every future call of the function.

所以,默认参数的逻辑相当于:

HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__ = []

bus1 = HauntedBus(HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__)

# bus1.passengers = HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__ (==[])

bus1.pick('Alice')

# bus1.passengers.append('Alice')

# ALSO changes HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__

bus2 = HauntedBus(HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__)

# bus2.passengers = HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__ (==['Alice'])

The issue with mutable defaults explains why None is often used as the default value for parameters that may receive mutable values. Best practice:

class Bus:

def __init__(self, passengers=None):

if passengers is None:

self.passengers = []

else:

self.passengers = list(passenger) # or deep copy if necessary

8.4.2 Defensive Programming with Mutable Parameters

When you are coding a function that receives a mutable parameter, you should carefully consider whether the caller expects the argument passed to be changed.

8.5 del and Garbage Collection

The del statement deletes names, not objects. An object may be garbage collected as result of a del command, but only if the variable deleted holds the last reference to the object, or if the object becomes unreachable. Rebinding a variable may also cause the number of references to an object to reach zero, causing its destruction.

N.B. __del__ is invoked by the Python interpreter when the instance is about to be destroyed to give it a chance to release external resources. You will seldom need to implement __del__ in your own code. (感觉和 java 里面你不需要去写 finalize() 差不多)

- In CPython, the primary algorithm for garbage collection is reference counting. As soon as that refcount reaches 0, the object is immediately destroyed: CPython calls the

__del__method on the object (if defined) and then frees the memory allocated to the object. - In CPython 2.0, a generational garbage collection algorithm was added to detect groups of objects involved in reference cycles–which may be unreachable even with outstand‐ ing references to them, when all the mutual references are contained within the group.

To demonstrate the end of an object’s life, the following example uses weakref.finalize to register a callback function to be called when an object is destroyed.

>>> import weakref

>>> s1 = {1, 2, 3}

>>> s2 = s1

>>> def bye():

... print('Gone with the wind...')

...

>>> ender = weakref.finalize(s1, bye)

>>> ender.alive

True

>>> del s1

>>> ender.alive

True

>>> s2 = 'spam'

Gone with the wind...

>>> ender.alive

False

8.6 Weak References

概念可以参考 Understanding Weak References.

Weak references to an object do not increase its reference count. The object that is the target of a reference is called the referent. Therefore, we say that a weak reference does not prevent the referent from being garbage collected.

8.6.1 The WeakValueDictionary Skit

The class WeakValueDictionary implements a mutable mapping where the values are weak references to objects. When a referent is garbage collected elsewhere in the program, the corresponding key is automatically removed from WeakValueDictionary. This is commonly used for caching.

8.6.2 Limitations of Weak References

Not every Python object may be the referent of a weak reference.

- Basic list and dict instances may not be referents, but a plain subclass of either can solve this problem easily.

intand tuple instances cannot be referents of weak references, even if subclasses of those types are created.

Most of these limitations are implementation details of CPython that may not applyother Python iterpreters.

8.7 Tricks Python Plays with Immutables

The sharing of string literals is an optimization technique called interning. CPython uses the same technique with small integers to avoid unnecessary duplication of “popular” numbers like 0, –1, and 42. Note that CPython does not intern all strings or integers, and the criteria it uses to do so is an undocumented implementation detail.

Chapter 9 - A Pythonic Object

9.1 Object Representations

__repr__(): returns a string representing the object as the developer wants to see it.__str__(): returns a string representing the object as the user wants to see it.__byte__(): called bybyte()to get the object represented as a byte sequence__format__(): called byforamt()orstr.format()to get string displays using special formatting codes

9.2 Vector Class Redux

没啥特别的,注意写法:

class Vector2d:

typecode = 'd'

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = float(x)

self.y = float(y)

def __iter__(self):

return (i for i in (self.x, self.y))

def __repr__(self):

class_name = type(self).__name__ # 考虑到继承;灵活获取 class name 而不是写死

return '{}({!r}, {!r})'.format(class_name, *self)

def __str__(self):

return str(tuple(self))

def __bytes__(self):

return (bytes([ord(self.typecode)]) + bytes(array(self.typecode, self)))

def __eq__(self, other):

return tuple(self) == tuple(other)

def __abs__(self):

return math.hypot(self.x, self.y)

def __bool__(self):

return bool(abs(self))

*self展开这个写法帅气~- 注意

*foo要求foo是个 iterable (上面有__iter__()所以满足条件) __iter__()要求返回一个 iterator,上面例子里返回的是一个 generator (from a generator expression)- 注意它不是 tuple-comp,因为 python 不存在 tuple-comp 这种东西

- 然后根据 Iterables vs. Iterators vs. Generators 我们得知 a generator is always a iterator,所以这个

__iter__()写法成立 - 还有一种写法也可以:

yield self.x; yield.self.y

9.3 classmethod vs staticmethod

先上例子:

class Demo:

@classmethod

def class_method(*args):

return args

@staticmethod

def static_method(*args):

return args

>>> Demo.class_method()

(<class __main__.Demo at 0x7f206749d6d0>,)

>>> Demo.class_method('Foo')

(<class __main__.Demo at 0x7f206749d6d0>, 'Foo')

>>> Demo.static_method()

()

>>> Demo.static_method('Foo')

('Foo',)

@staticmethod好理解@classmethod第一个参数必定是 class 本身- 注意这里 “class 本身” 指的是

Demo而不是Demo.__class__ - 所以类似成员 method 第一个参数默认写

self一样,@classmethod第一个参数默认写clsdef member_method(self, *args)def class_method(cls, *args)

- 这个

cls可以当 constructor 用

- 注意这里 “class 本身” 指的是

class Demo:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

@classmethod

def class_method(cls, value):

return cls(value)

d = Demo.class_method(2)

print(d.value) # Output: 2

9.4 Making It Hashable

To make Vector2d hashable, we must

- Implement

__hash__()__eq__()is also required then

- Make it immutable

To make Vector2d, we can only expose the getters, like

class Vector2d:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.__x = float(x)

self.__y = float(y)

@property

def x(self):

return self.__x

@property

def y(self):

return self.__y

v = Vector2d(3, 4)

print(v.x) # accessible

# v.x = 7 # forbidden!

9.4.1 Digress: @property / __getattribute__() / __get__()

要想搞清楚 @property 的工作原理,我们需要先搞清楚 b.x 这样一个访问 object 字段的表达式是如何被解析的:

b.x$\Rightarrow$b.__getattribute__('x')- CASE 1:

b.__dict__['x']has defined__get__()$\Rightarrow$b.__dict__['x'].__get__(b, type(b))- 若是访问 static member

B.x则会变成B.__dict__['x'].__get__(None, B)

- 若是访问 static member

- CASE 2:

b.__dict__['x']has not defined__get__()$\Rightarrow$ just returnb.__dict__['x']- 若是访问 static member

B.x则会变成B.__dict__['x']

- 若是访问 static member

- CASE 1:

如果没有用 @property,一般的 b.x 都是 CASE 2,因为一般的 int、string 这些基础类型都没有实现 __get__();用了 @property 的话,就是强行转成了 CASE 1,因为 property(x) 返回的是一个 property 对象,它是自带 __get__ 方法的。

N.B. 我们称实现了以下三个方法的类型为 descriptor

__get__(self, obj, type=None) --> value__set__(self, obj, value) --> None__delete__(self, obj) --> None

@property 类型是 descriptor.

我们来看一下代码分解:

class B:

@property

def x(self):

return self.__x

# ----- Is Equivalent To ----- #

property_x = property(fget=x)

x = __dict__['x'] = property_x

然后就有

b.x- $\Rightarrow$

b.__dict__['x'].__get__(b, type(b))- $\Rightarrow$

property_x.__get__(b, type(b))- $\Rightarrow$

property_x.fget(b)- $\Rightarrow$ 实际调用原始的

x(b)方法 (TMD 又绕回去了) - 注意:此时

b.x()方法是调用不到的,因为b.x被优先解析了;这里property_x内部还能调用x(b)是因为它保存了这个原始的def x(self)方法

- $\Rightarrow$ 实际调用原始的

- $\Rightarrow$

- $\Rightarrow$

- $\Rightarrow$

这里最 confusing 的地方在于:b.x 从一个 method 变成了一个 property 对象,而且屏蔽掉了对 b.x() 方法的访问。一个不那么 confusing 的写法是:

class B:

def get_x(self):

return self.__x

x = property(fget=get_x, fset=None, fdel=None, "Docstring here")

9.4.2 Digress Further: x.setter / x.deleter

代码分解:

# python 2 需要继承 `object` 才是 new-style class

# python 3 默认是 new-style class,继不继承 `object` 无所谓

# `x.setter` 和 `x.deleter` 需要在 new-style class 内才能正常工作

class B(object):

def __init__(self):

self._x = None

@property

def x(self): # method-1

"""I'm the 'x' property."""

return self._x

@x.setter

def x(self, value): # method-2

self._x = value

@x.deleter

def x(self): # method-3

del self._x

# ----- Is Equivalent To ----- #

x = property(fget=x) # 屏蔽了对 method-1 的访问

x = x.setter(x) # 屏蔽了对 method-2 的访问

# 实际是返回了原来 property 的 copy,并设置了 `fset`

# x = property(fget=x.fget, fset=x)

x = x.deleter(x) # 屏蔽了对 method-3 的访问

# 实际是返回了原来 property 的 copy,并设置了 `fdel`

# x = property(fget=x.fget, fset=x.fset, fdel=x)

不那么 confusing 的写法:

class B(object):

def __init__(self):

self._x = None

def get_x(self):

return self._xshiyong

def set_x(self, value):

self._x = value

def del_x(self):

del self._x

x = property(fset=get_x, fset=set_x, fdel=del_x, "Docstring here")

9.4.3 __hash__()

The __hash__ special method documentation suggests using the bitwise XOR operator (^) to mix the hashes of the components.

class Vector2d:

def __eq__(self, other):

return tuple(self) == tuple(other)

def __hash__(self):

return hash(self.x) ^ hash(self.y)

9.5 “Private” and “Protected”

To prevent accidental overwritting of a private attribute of a class, python would store __bar attribute of class Foo in Foo.__dict__ as _Foo__bar. This language feature is called name mangling.

Name mangling is about safety, not security: it’s designed to prevent accidental access and not intentional wrongdoing.

name mangling 不会处理 __foo__ 这样前后都有双下划线的 name.

The single underscore prefix, like _bar, has no special meaning to the Python interpreter when used in attribute names, but it’s a very strong convention among Python programmers that you should not access such attributes from outside the class.

补充:If you use a wildcard import (from pkg import *) to import all the names from the module, Python will not import names with a leading underscore (unless the module defines an __all__ list that overrides this behavior). 从这个角度来讲,wildcard import 应该慎用。

9.6 Saving Space with the __slots__ Class Attribute

By default, Python stores instance attributes in a per-instance dict named __dict__. Dictinaries have a significant memory overhead, especially when you are dealing with millions of instances with few attributes. The __slots__ class attribute can save a lot of memory, by letting the interpreter store the instance attributes in a tuple instead of a dict.

A __slots__ attribute inherited from a superclass has no effect. Python only takes into account slots attributes defined in each class individually.

class Vector2d:

__slots__ = ('__x', '__y')

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.__x = float(x)

self.__y = float(y)

When __slots__ is specified in a class, its instances will not be allowed to have any other attributes apart from those named in __slots__. It’s considered a bad practice to use __slots__ just to prevent users of your class from creating new attributes. __slots__ should used for optimization, not for programmer restraint.

It may be possible, however, to “save memory and eat it too”: if you add __dict__ to the __slots__ list, your instances will keep attributes named in __slots__ in the per-instance tuple, but will also support dynamically created attributes, which will be stored in the usual __dict__, entirely defeating __slots__’s purpose.

There is another special per-instance attribute that you may want to keep: the __weak ref__ attribute, which exists by default in instances of user-defined classes. However, if the class defines __slots__, and you need the instances to be target of weak references, then you need to include __weakref__ among the attribute named in __slots__.

9.7 Overriding Class Attributes

比如前面的 typecode = 'd' 和 __slots__ 这样不带 self 初始化的都是 class attributes,类似 java 的 static.

If you write to an instance attribute that does not exist, you create a new instance attribute. 假设你有一个 class attribute Foo.bar 和 instance f,正常情况下 f.bar 可以访问到 Foo.bar,但你可以重新赋值 f.bar = 'baz' 从而覆盖掉原有的 f.bar 的值,同时 class attribute Foo.bar 不会受影响。这实际上提供了一种新的继承和多态的思路 (不用把 bar 设计成 Foo 的 instance attribute)。

Chapter 10 - Sequence Hacking, Hashing, and Slicing

In this chapter, we will create a class to represent a multidimensional Vector class — a significant step up from the two-dimensional Vector2d of Chapter 9.

10.1 Vector Take #1: Vector2d Compatible

先说个题外话,你在 console 里面直接输入 f 然后回车,调用的是 f.__repr__(),而 print(f) 调用的是 f.__str__() (如果有定义的话;没有的话还是会 fall back 到 f.__repr__())

>>> class Foo:

... def __repr__(self):

... return "Running Foo.__repr__()"

... def __str__(self):

... return "Running Foo.__str__()"

...

>>> f = Foo()

>>> f

Running Foo.__repr__()

>>> print(f)

Running Foo.__str__()

这也说明一点:你在 debug 的时候不应该把 __repr__ 设计得太复杂,想想一下满屏的字符串看起来是有多头痛。

from array import array

import reprlib

import math

class Vector:

typecode = 'd'

def __init__(self, components):

self._components = array(self.typecode, components)

def __iter__(self):

return iter(self._components)

def __repr__(self):

components = reprlib.repr(self._components)

components = components[components.find('['):-1]

return 'Vector({})'.format(components)

def __str__(self):

return str(tuple(self))

def __bytes__(self):

return (bytes([ord(self.typecode)]) + bytes(self._components))

def __eq__(self, other):

return tuple(self) == tuple(other)

def __abs__(self):

return math.sqrt(sum(x * x for x in self))

def __bool__(self):

return bool(abs(self))

@classmethod

def frombytes(cls, octets):

typecode = chr(octets[0])

memv = memoryview(octets[1:]).cast(typecode)

return cls(memv)

上面这个 __repr__ 的处理就很值得学习:reprlib.repr() 的返回值类似 array('d', [0.0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, ...]),超过 6 个元素就会用省略号表示;然后上面的代码再截取出 [...] 的部分然后格式化输出。

Digress: Protocols and Duck Typing

In the context of object-oriented programming, a protocol is an informal interface, defined only in documentation and not in code. 简单说,只要实现了 protocol 要求的函数,你就是 protocol 的实现,并不用显式声明你要实现这个 protocol (反例就是 java 的 interface).

Duck Typing 的源起:

Don’t check whether it is-a duck: check whether it quacks-like-a duck, walks-like-a duck, etc, etc, depending on exactly what subset of duck-like behavior you need to play your language-games with. (comp.lang.python, Jul. 26, 2000) — Alex Martelli

简单说就是 python 并不要求显式声明 is-a (当然你要显式也是可以的 — 用 ABC,但是需要注意不仅限于 abc.ABC,还有 collections.abc 等细分的 ABC,比如 MutableSequence;参 11.3 章节),like-a 在 python 里等同于 is-a.

10.2 Vector Take #2: A Sliceable Sequence

Basic sequence protocol: __len__ and __getitem__:

class Vector:

def __len__(self):

return len(self._components)

def __getitem__(self, index):

return self._components[index]

>>> v1 = Vector([3, 4, 5])

>>> len(v1)

3

>>> v1[0], v1[-1]

(3.0, 5.0)

>>> v7 = Vector(range(7))

>>> v7[1:4]

array('d', [1.0, 2.0, 3.0]) # It would be better if a slice of Vector is also a Vector

10.2.1 How Slicing Works

>>> class MySeq:

... def __getitem__(self, index):

... return index

...

>>> s = MySeq()

>>> s[1]

1

>>> s[1:4]

slice(1, 4, None)

>>> s[1:4:2]

slice(1, 4, 2)

>>> s[1:4:2, 9]

(slice(1, 4, 2), 9)

>>> s[1:4:2, 7:9]

(slice(1, 4, 2), slice(7, 9, None))

可以看到:

s[1]$\Rightarrow$s.__getitem__(1)s[1:4]$\Rightarrow$s.__getitem__(slice(1, 4, None))s[1:4:2]$\Rightarrow$s.__getitem__(slice(1, 4, 2))s[1:4:2, 9]$\Rightarrow$s.__getitem__((slice(1, 4, 2), 9))s[1:4:2, 7:9]$\Rightarrow$s.__getitem__((slice(1, 4, 2), slice(7, 9, None)))

slice is a built-in type. slice(1, 4, 2) means “start at 1, stop at 4, step by 2”. dir(slice) you’ll find 3 attributes, start, stop, step and 1 method, indices.

假设有一个 s = slice(...),那么 s.indices(n) 的作用就是:当我们用 s 去 slice 一个长度为 n 的 sequence 时,s.indices(n) 会返回一个 tuple (start, stop, step) 表示这个 sequence-specific 的 slice 信息。举个例子说:slice(0, None, None) 是一个 general 的 slice,但当它作用于一个长度为 5 和一个长度为 7 的 sequence 时,它内部的逻辑是不一样的,一个会变成 [1:5] 另一个会变成 [1:7]。

>>> s = slice(0, None, None)

>>> s.indices(5)

(0, 5, 1)

>>> s.indices(7)

(0, 7, 1)

slice 有很多类似这样的 “智能的” 处理方法,比如 “如果 step 比 n 还要大的时候该怎么办”;可以参考这篇

The Intelligence Behind Python Slices.

另外需要注意的是,如果你自己去实现一个 sequence from scratch,你可能需要类似 Extended Slices 上这个例子的实现:

class FakeSeq:

def calc_item(self, i):

"""Return the i-th element"""

def __getitem__(self, item):

if isinstance(item, slice):

indices = item.indices(len(self))

return FakeSeq([self.calc_item(i) for i in range(*indices)])

else:

return self.calc_item(i)

如果你是组合了一个 built-in sequence 来实现自己的 sequence,你就不需要用到 s.indices(n) 方法,因为可以直接 delegate 给这个 built-in sequence 去处理,书上的例子就是这样的,见下。

10.2.2 A Slice-Aware __getitem__

def __getitem__(self, index):

cls = type(self)

if isinstance(index, slice):

return cls(self._components[index])

elif isinstance(index, numbers.Integral):

return self._components[index]

else:

msg = '{cls.__name__} indices must be integers'

raise TypeError(msg.format(cls=cls))

10.3 Vector Take #3: Dynamic Attribute Access

我们想保留 “用 x, y, z 和 t 来指代一个 vector 的前 4 个维度” 这么一个 convention,换言之我们想要有 v.x == v[0] etc.

方案一:用 @property 去写 4 个 getter

方案二:用 __getattr__。等 v.x 这个 attribute lookup fails,然后 fall back 到 __getattr__ 处理。这个方案更灵活。

shortcut_names = 'xyzt'

def __getattr__(self, name):

cls = type(self)

if len(name) == 1:

pos = cls.shortcut_names.find(name)

if 0 <= pos < len(self._components):

return self._components[pos]

msg = '{.__name__!r} object has no attribute {!r}'

raise AttributeError(msg.format(cls, name))

但是这么一来会引入一个新的问题:你如何处理 v.x = 10 这样的赋值?是允许它创建一个新的 attribute x?还是去修改 v[0] 的值?

如果你允许它创建新的 attribute x,那么下次 v.x 就不会 fall back 到 __getattr__ 了。去修改 v[0] 我觉得是可行的,但是书上决定把 v.x 到 v.t 这 4 个 attribute 做成 read-only,同时禁止创建名字为单个小写字母的 attribute。这些逻辑的去处是 __setattr__:

def __setattr__(self, name, value):

cls = type(self)

if len(name) == 1:

if name in cls.shortcut_names:

error = 'readonly attribute {attr_name!r}'

elif name.islower():

error = "can't set attributes 'a' to 'z' in {cls_name!r}"

else:

error = ''

if error:

msg = error.format(cls_name=cls.__name__, attr_name=name)

raise AttributeError(msg)

super().__setattr__(name, value) # 正常创建名字合法的 attribute

如果你要限定允许的 attribute name,一个可以 work 的方案是用 __slots__,但如同前面所说的,这个用途违背了 __slots__ 的设计初衷,不推荐使用。

10.4 Vector Take #4: Hashing and a Faster ==

import functools

import operator

class Vector:

def __eq__(self, other): #

return tuple(self) == tuple(other)

def __hash__(self):

# Generator expression!

# Lazily compute the hash of each component.

# 可以省一点空间,相对于 List 而言 (只占用一个元素的内存,而不是一整个 list 的)

hashes = (hash(x) for x in self._components)

return functools.reduce(operator.xor, hashes, 0)

When using reduce, it’s good practice to provide the third argument, reduce(function, iterable, initializer), to prevent this exception: TypeError: reduce() of empty sequence with no initial value (excellent message: explains the problem and how to fix it). The initializer is the value returned if the sequence is empty and is used as the first argument in the reducing loop, so it should be the identity value of the operation. As examples, for +, |, ^ the initializer should be 0, but for *, & it should be 1.

这个 __hash__ 的实现也是很好的 map-reduce 的例子:apply function to each item to generate a new series (map), then compute aggregate (reduce)。用下面这个写法就更明显了:

def __hash__(self):

hashes = map(hash, self._components)

return functools.reduce(operator.xor, hashes, 0)

对 high-dimensional 的 vector,我们的 __eq__ 性能可能会有问题。一个更好的实现是:

def __eq__(self, other):

if len(self) != len(other):

return False

for a, b in zip(self, other):

if a != b:

return False

return True

# ----- Even Better ----- #

def __eq__(self, other):

return len(self) == len(other) and all(a == b for a, b in zip(self, other))

10.5 Vector Take #5: Formatting (略)

Chapter 11 - Interfaces: From Protocols to ABCs

11.1 Monkey-Patching to Implement a Protocol at Runtime

Monkey patch refers to dynamic modifications of a class or module at runtime, motivated by the intent to patch existing third-party code as a workaround to a bug or feature which does not act as desired.

比如我们第一章的 FrenchDeck 不支持 shuffle() 操作,error 告诉我们底层原因是因为没有支持 __setitem__:

>>> from random import shuffle

>>> from frenchdeck import FrenchDeck

>>> deck = FrenchDeck()

>>> shuffle(deck)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File ".../python3.3/random.py", line 265, in shuffle

x[i], x[j] = x[j], x[i]

TypeError: 'FrenchDeck' object does not support item assignment

所以我们可以直接在 runtime 里给 FrenchDeck 加一个 __setitem__ 而不用去修改它的源代码:

>>> def set_card(deck, position, card):

... deck._cards[position] = card

...

>>> FrenchDeck.__setitem__ = set_card

>>> shuffle(deck)

有点像给 JS 元素动态添加 event-listener。

11.2 Subclassing an ABC

Python does not check for the implementation of the abstract methods at import time, but only at runtime when we actually try to instantiate the subclass.

11.3 ABCs in the Standard Library

Every ABC depends on abc.ABC, but we don’t need to import it ourselves except to create a new ABC.

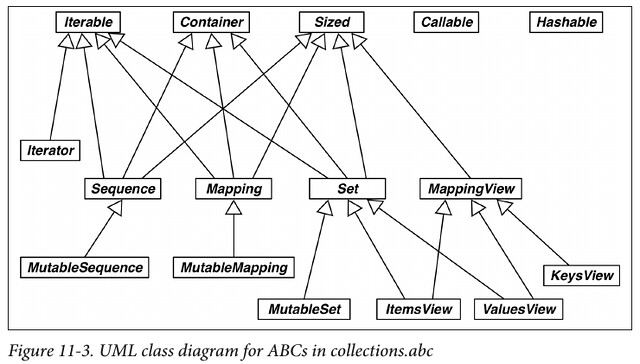

11.3.1 ABCs in collections.abc

更详细的说明见 Python documentation - 8.4.1. Collections Abstract Base Classes

11.3.2 The numbers Tower of ABCs

numbers package 有如下的的继承关系:

Number- $\Uparrow$

Complex(A complex number is a number of the form $a + bi$, where $a$ and $b$ are real numbers and $i$ is the imaginary unit.)- $\Uparrow$

Real(A real number can be seen as a special complex where $b=0$; the real numbers include all the rational numbers and all the irrational numbers.)- $\Uparrow$

Rational(A Rational Number is a real number that can be written as a simple fraction, i.e. as a ratio. 反例:$\sqrt 2$)- $\Uparrow$

Integral

- $\Uparrow$

- $\Uparrow$

- $\Uparrow$

- $\Uparrow$

另外有:

int实现了numbers.Integral,然后boolsubclassesint,所以isinstance(x, numbers.Integral)对int和bool都有效isinstance(x, numbers.Real)对bool、int、float、fractions.Fraction都有效 (所以这不是一个很好的 check ifxis float 的方法)- However,

decimal.Decimal并没有实现numbers.Real

- However,

11.4 Defining and Using an ABC

An abstract method can actually have an implementation. Even if it does, subclasses will still be forced to override it, but they will be able to invoke the abstract method with super(), adding functionality to it instead of implementing from scratch.

注意版本问题:

import abc

# ----- Python 3.4 or above ----- #

class Foo(abc.ABC):

pass

# ----- Before Python 3.4 ----- #

class Foo(metaclass=abc.ABCMeta): # No `abc.ABC` before Python 3.4

pass

# ----- Holy Python 2 ----- #

class Foo(object): # No `metaclass` argument in Python 2

__metaclass__ = abc.ABCMeta

pass

Python 3.4 引入的逻辑其实是 def abc.ABC(metaclass=abc.ABCMeta)

另外 @abc.abstractmethod 必须是 innermost 的 decorator (i.e. 它与 def 之间不能再有别的 decorator)

11.5 Virtual Subclasses

我第一个想到的是 C++: Virtual Inheritance,但是在 python 这里 virtual subclass 根本不是这个意思。

python 的 virtual subclass 简单说,就是你的 VirtualExt 在 issubclass 和 isinstance 看来都是 Base 的子类,但实际上 VirtualExt 并不继承 Base,即使 Base 是 ABC,VirtualExt 也不用实现 Base 要求的接口。

不过说实话,你 issubclass 和 isinstance 都已经判断成子类了,我想不出你不用这个多态的理由……

具体写法:

import abc

class Base(abc.ABC):

def __init__(self):

self.x = 5

@abc.abstractmethod

def foo():

"""Do nothing"""

class TrueBase():

def __init__(self):

self.y = 5

@Base.register

class VirtualExt(TrueBase):

pass

>>> issubclass(VirtualExt, Base)

True

>>> issubclass(VirtualExt, TrueBase)

True

>>> ve = VirtualExt()

>>> isinstance(ve, Base)

True

>>> isinstance(ve, TrueBase)

True

>>> ve.x

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'VirtualExt' object has no attribute 'x'

>>> ve.foo()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'VirtualExt' object has no attribute 'foo'

>>> ve.y

5

说明一下:

Base.register()其实是继承自abc.ABC.register(),意思是 “把VirtualExtregister 成Base的子类,with no doubt”- 进一步说明你只能 virtually 继承一个 ABC

issubclass(VirtualExt, Base) == True和isinstance(ve, Base) == True都成立但是VirtualExt既没有 attributex也没有实现foo- 所以说这是一个 “假” 继承 (我觉得叫 Fake Inheritance 更合适……)

class VirtualExt(TrueBase)这是一个 真·继承- 这里也不是多重继承

- 多重继承你得写成

class MultiExt(Base, TrueBase)

- 多重继承你得写成

Inheritance is guided by a special class attribute named __mro__, the Method Resolution Order. It basically lists the class and its superclasses in the order Python uses to search for methods.

>>> VirtualExt.__mro__

(<class '__main__.VirtualExt'>, <class '__main__.TrueBase'>, <class 'object'>)

Base is not in VirtualExt.__mro__. 这进一步验证了我们的结论:VirtualExt 并没有实际继承 Base。

11.5.1 issubclass Alternatives: __subclasses__ and _abc_registry

Base.__subclasses__()(注意这是一个方法)- 返回所有

Base的 immediate 子类 (即不会递归去找子类的子类)- 没有 import 进来的子类是不可能被找到的

- 不会列出 virtual 子类

- 不 care

Base是不是 ABC

- 返回所有

Base._abc_registry(注意这是一个attribute)- 要求

Base是 ABC - 返回所有

Base的 virtual 子类 - 返回值类型其实是一个

WeakSet,元素是 weak references to virtual subclasses

- 要求

11.5.2 __subclasshook__

- 必须是一个

@classmethod - 写在 ABC 父类中,如果

Base.__subclasshook__(Ext) == True,则issubclass(Ext, Base) == True- 注意这是由父类直接控制

issubclasses的逻辑 - 不需要走

Base.register()

- 注意这是由父类直接控制

书上的例子是 collections.abc.Sized,它的逻辑是:只要是实现了 __len__ 方法的类都是我 Sized 的子类:

class Sized(metaclass=ABCMeta):

__slots__ = ()

@abstractmethod

def __len__(self):

return 0

@classmethod

def __subclasshook__(cls, C):

if cls is Sized:

if any("__len__" in B.__dict__ for B in C.__mro__):

return True

return NotImplemented # See https://docs.python.org/3/library/constants.html

但是在你自己的 ABC 业务类中并不推荐使用 __subclasshook__,因为它太底层了,多用于 lib 设计中。

Chapter 12 - Inheritance: For Good or For Worse

本章谈两个问题:

- The pitfalls of subclassing from built-in types

- Multiple inheritance and the method resolution order

12.1 Subclassing Built-In Types Is Tricky

一个很微妙的问题:你无法确定底层函数的调用逻辑。举个例子,我们之前有说 getattr(obj, name) 的逻辑是先去取 obj.__getattribute__(name)。所以正常的想法是:我子类如果覆写了 __getattribute__,那么 getattr 作用在子类上的行为也会相应改变。但是实际情况是:getattr 不一定会实际调用 __getattribute__ (比如说有可能去调用公用的更底层的逻辑)。而且这个行为是 language-implementation-specific 的,所以有可能 PyPy 和 CPython 的逻辑还不一样。

Differences between PyPy and CPython » Subclasses of built-in types:

Officially, CPython has no rule at all for when exactly overridden method of subclasses of built-in types get implicitly called or not. As an approximation, these methods are never called by other built-in methods of the same object. For example, an overridden

__getitem__()in a subclass ofdictwill not be called by e.g. the built-inget()method.

Subclassing built-in types like dict or list or str directly is error-prone because the built-in methods mostly ignore user-defined overrides. Instead of subclassing the built-ins, derive your classes from the collections module using UserDict, UserList, and UserString, which are designed to be easily extended.

12.2 Multiple Inheritance and Method Resolution Order

首先 python 没有 C++: Virtual Inheritance 里的 dread diamond 问题,子类 D 定位到父类 A 的方法毫无压力,而且查找顺序是固定的–以 D.__mro__ 的顺序为准。

另外需要注意的是,等价于 instance.method(),Class.method(instance) 这种有点像 static 的写法的也是可行的:

>>> class Foo:

... def bar(self):

... print("bar")

...

>>> f = Foo()

>>> f.bar()

bar

>>> Foo.bar(f)

bar

所以可以衍生出 Base.method(ext) 这种写法,相当于在子类对象 ext 上调用父类 Base 的方法。当然更好的写法是在 Ext 里用 super().method()。

从上面这个例子出发,我们还可以引申出另外一个问题:既没有 self 参数也没有标注 @staticmethod 的方法是怎样的存在?

>>> class Foo:

... def bar():

... print("bar")

... @staticmethod

... def baz():

... print("baz")

...

>>> f = Foo()

>>> f.bar()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: bar() takes 0 positional arguments but 1 was given

>>> f.baz()

baz

>>> Foo.bar()

bar

>>> Foo.baz()

baz

可见:

- 对成员方法

bar:f.bar()会无脑转换成Foo.bar(f)- 所以如果不给

bar定一个self参数的话,它就不可能成为一个成员方法,而是成了一个 ”只能通过Foo访问的” static 方法

- 所以如果不给

- 对 static 方法

baz:f.baz()转换成Foo.baz()这是顺理成章的

12.3 Coping with Multiple Inheritance

- Distinguish Interface Inheritance from Implementation Inheritance

- Make Interfaces Explicit with ABCs

- Use Mixins for Code Reuse

- Conceptually, a mixin does not define a new type; it merely bundles methods for reuse.

- A mixin should never be instantiated, and concrete classes should not inherit only from a mixin.

- Eachs mixin should provide a single specific behavior, implementing few and very closely related methods.

- Make Mixins Explicit by Naming

- An ABC May Also Be a Mixin; The Reverse Is Not True

- Don’t Subclass from More Than One Concrete Class

- Provide Aggregate Classes to Users

- If some combination of ABCs or mixins is particularly useful to client code, provide a class that brings them together in a sensible way. Grady Booch calls this an aggregate class.

- “Favor Object Composition Over Class Inheritance.”

- Universally true.

Chapter 13 - Operator Overloading: Doing It Right

13.1 Operator Overloading 101

Python limitation on operator overloading:

- We cannot overload operators for the built-in types.

- We cannot create new operators, only overload existing ones.

- A few operators can’t be overloaded:

is,and,or,not(but the bitwise&,|,~, can).

13.2 Unary Operators

+$\Rightarrow$__pos__-$\Rightarrow$__neg__~$\Rightarrow$__invert__- Bitwise inverse of an integer, defined as

~x == -(x+1)

- Bitwise inverse of an integer, defined as

abs$\Rightarrow$__abs__

When implementing, always return a new object instead of modifying self.

13.3 + for Vector Addition

import itertools

def __add__(self, other):

pairs = itertools.zip_longest(self, other, fillvalue=0.0)

return Vector(a + b for a, b in pairs)

zip_longest这个是见识到了!这么一来 length 不同的 Vector 也可以相加了other没有类型限制,但是要注意这么一来有个加法顺序的问题:Vector([1, 2]) + (3, 4)是 OK 的,等同于v.__add__((3, 4))- 反过来

(3, 4) + Vector([1, 2])就不行,因为 tuple 的__add__处理不了 Vector- 而且 tuple 的加法是被设计成 concat 的,

(1, 2) + (3, 4) == (1, 2, 3, 4)

- 而且 tuple 的加法是被设计成 concat 的,

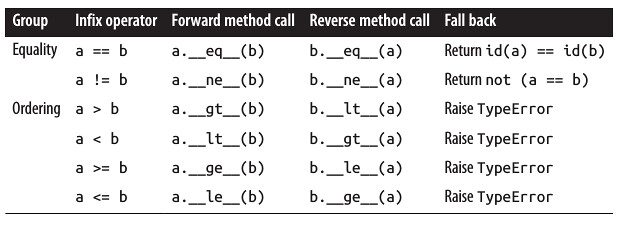

To support operations involving objects of different types, Python implements a special dispatching mechanism for the infix operator special methods. Given an expression a + b, the interpreter will perform these steps:

- Call

a.__add__(b). - If

adoesn’t have__add__, or calling it returnsNotImplemented, callb.__radd__(a).__radd__means “reflected”, “reversed” or “right” version of__add__- 同理还有

__rsub__

- If

bdoesn’t have__radd__, or calling it returnsNotImplemented, raiseTypeErrorwith anunsupported operand typesmessage.

所以加一个 __radd__ 就可以解决 (3, 4) + Vector([1, 2]) 的问题:

def __radd__(self, other):

return self + other

注意这里的逻辑:tuple.__add__(vector) $\Rightarrow$ vector.__radd__(tuple) $\Rightarrow$ vector.__add__(tuple)。

另外一个需要注意的是:如何规范地 return NotImplemented?示范代码:

def __add__(self, other):

try:

pairs = itertools.zip_longest(self, other, fillvalue=0.0)

return Vector(a + b for a, b in pairs)

except TypeError:

return NotImplemented

13.4 * for Scalar Multiplication

这里我们限制一下乘数的类型:

import numbers

def __mul__(self, scalar):

if isinstance(scalar, numbers.Real):

return Vector(n * scalar for n in self)

else:

return NotImplemented

def __rmul__(self, scalar):

return self * scalar

Digress: @ for Matrix Multiplication since Python 3.5

>>> import numpy as np

>>> va = np.array([1, 2, 3])

>>> vb = np.array([5, 6, 7])

>>> va @ vb # 1*5 + 2*6 + 3*7

38

>>> va.dot(vb)

38

Digress: __ixxx__ Series In-place Operators

比如 a += 2 其实就是 a.__iadd__(2)。

另外注意 python 没有 a++ 和 ++a 这样的操作

13.5 Rich Comparison Operators

reverse 的逻辑还是一样的:如果 a.__eq__(b) 行不通就调用 b.__eq__(a)。需要注意 type checking 的情景,因为有可能存在继承关系:

- 比如

ext.__eq__(base) == False因为isinstace(base, Ext) == False - 此时反过来跑去调用

base.__eq__(ext),结果isintace(ext, Base) == True,而且后续的比较也都 OK,最后还是返回了True - 相当于强行要求你考虑 reflexivity 自反性

13.6 Augmented Assignment Operators

If a class does not implement the in-place operators, the augmented assignment operators are just syntactic sugar: a += b is evaluated exactly as a = a + b. That’s the expected behavior for immutable types, and if you have __add__ then += will work with no additional code.

The in-place special methods should never be implemented for immutable types like our Vector class.

As the name says, these in-place operators are expected to change the lefthand operand in place, and not create a new object as the result.

留下评论