Digest of Fluent Python: Part V - Control Flow (iterables, iterators, generators, context managers, corotines, concurrency, asyncio)

Chapter 14 - Iterables, Iterators, and Generators

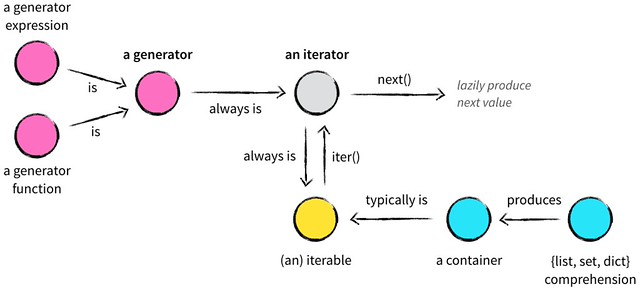

一篇很好的 blog 以供参考:nvie.com: Iterables vs. Iterators vs. Generators

14.1 Sentence Take #1: A Sequence of Words

import re

import reprlib

RE_WORD = re.compile('\w+')

class Sentence:

def __init__(self, text):

self.text = text

self.words = RE_WORD.findall(text)

def __getitem__(self, index):

return self.words[index]

def __len__(self):

return len(self.words)

def __repr__(self):

return 'Sentence(%s)' % reprlib.repr(self.text)

Whenever the interpreter needs to iterate over an object x, it automatically calls iter(x). It runs like:

- Call

x.__iter__()to obtain an iterator. - If

__iter__()is not implemented inx, Python tries to create an iterator that attempts to fetch items in order, usingx.__getitem__() - If that fails too, Python raises

TypeError, usually saying “Xobject is not iterable”.

所以即使 python sequence 类没有实现 __iter__,它们自带的 __getitem__ 也能保证它们是 iterable 的。

另外,collections.abc.Iterable 在它的 __subclasshook__ 中认定:所有实现了 __iter__ 的类都是 collections.abc.Iterable 的子类。

14.2 Iterables Versus Iterators

Any object from which the iter() built-in function can obtain an iterator is an iterable.

The standard interface for an iterator has two methods:

__next__- Returns the next available item, raising

StopIterationwhen there are no more items.

- Returns the next available item, raising

__iter__- Returns

self; this allows iterators to be used where an iterable is expected, for example, in a for loop. - 根据 iterable 的定义,iterator 本身也是 iterable

- Returns

for i in seq:

do_something(i)

# ----- Is Equivalent To ----- #

it = iter(seq)

while True:

try:

i = next(it)

do_something(i)

except StopIteration:

del it

break

# Once exhausted, an iterator becomes useless.

# To go over the seq again, a new iterator must be built.

14.3 Sentence Take #2: A Classic Iterator

import re

import reprlib

RE_WORD = re.compile('\w+')

class Sentence:

def __init__(self, text):

self.text = text

self.words = RE_WORD.findall(text)

def __repr__(self):

return 'Sentence(%s)' % reprlib.repr(self.text)

def __iter__(self):

return SentenceIterator(self.words)

class SentenceIterator:

def __init__(self, words):

self.words = words

self.index = 0

def __next__(self):

try:

word = self.words[self.index]

except IndexError:

raise StopIteration()

self.index += 1

return word

def __iter__(self):

return self

14.4 Sentence Take #3: A Generator Function

import re

import reprlib

RE_WORD = re.compile('\w+')

class Sentence:

def __init__(self, text):

self.text = text

self.words = RE_WORD.findall(text)

def __repr__(self):

return 'Sentence(%s)' % reprlib.repr(self.text)

def __iter__(self):

for word in self.words:

yield word

# return # Not necessary

# done!

Any Python function that has the yield keyword in its body is a generator function: a function which, when called, returns a generator object. In other words, a generator

function is a generator factory.

Suppose generator function gen() returns a generator object g by g = gen(). When we invoke next(g), execution advances to the next yield in the gen() function body, and the next(g) call evaluates to the value yielded when the gen() is suspended. Finally, when gen() returns, g raises StopIteration, in accordance with the Iterator protocol.

14.5 Sentence Take #4: A Lazy Implementation

Nowadays, laziness is considered a good trait, at least in programming languages and APIs. A lazy implementation postpones producing values to the last possible moment. This saves memory and may avoid useless processing as well. (与 lazy evaluation 对应的是 eager evaluation)

import re

import reprlib

RE_WORD = re.compile('\w+')

class Sentence:

def __init__(self, text):

self.text = text

def __repr__(self):

return 'Sentence(%s)' % reprlib.repr(self.text)

def __iter__(self):

for match in RE_WORD.finditer(self.text):

yield match.group()

N.B. Whenever you are using Python 3 and start wondering “Is there a lazy way of doing this?”, often the answer is “Yes.”

14.6 Sentence Take #5: A Generator Expression

A generator expression can be understood as a lazy version of a listcomp.

import re

import reprlib

RE_WORD = re.compile('\w+')

class Sentence:

def __init__(self, text):

self.text = text

def __repr__(self):

return 'Sentence(%s)' % reprlib.repr(self.text)

def __iter__(self):

return (match.group() for match in RE_WORD.finditer(self.text))

Generator expressions are syntactic sugar: they can always be replaced by generator functions, but sometimes are more convenient.

Syntax Tip: When a generator expression is passed as the single argument to a function or constructor, you don’t need to write its parentheses.

>>> (i * 5 for i in range(1, 5))

<generator object <genexpr> at 0x7f54bf32cdb0>

>>> list(i * 5 for i in range(1, 5))

[5, 10, 15, 20]

>>> list((i * 5 for i in range(1, 5)))

[5, 10, 15, 20]

14.7 Generator Functions in the Standard Library

参 Python Documentation: 10.1. itertools — Functions creating iterators for efficient looping

14.7.1 Create Generators Yielding Filtered Data

itertools.compress(Iterable data, Iterable mask): 类似于 numpy 的data[mask],只是返回结果是一个 generator- E.g.

compress([1, 2, 3], [True, False, True])returns a generator ofyield 1; yield 3

- E.g.

itertools.dropwhile(Function condition, Iterable data):dropxindatawhilecondition(x) == True; return a generator from the leftover indata- E.g.

dropwhile(lambda x: x <= 2, [1, 2, 3, 2, 1])returns a generator ofyield 3; yield 2; yield 1

- E.g.

itertools.takewhile(Function condition, Iterable data): yieldxindatawhilecondition(x) == True; stop yielding immediately oncecondition(x) == False- E.g.

takewhile(lambda x: x <= 2, [1, 2, 3, 2, 1])returns a generator ofyield 1; yield 2

- E.g.

- (built-in)

filter(Function condition, Iterable data): yieldxindataifcondition(x) == True itertools.filterfalse(Function condition, Iterable data): yieldxindataifcondition(x) == Falseitertools.islice(Iterable data[, start], stop[, step]): return a generator fromdata[start: stop: step]

def compress(data, mask):

# compress('ABCDEF', [1,0,1,0,1,1]) --> A C E F

return (d for d, m in zip(data, m) if m)

def dropwhile(condition, iterable):

# dropwhile(lambda x: x<5, [1,4,6,4,1]) --> 6 4 1

iterable = iter(iterable)

for x in iterable:

if not condition(x):

yield x

break

for x in iterable:

yield x

def takewhile(condition, iterable):

# takewhile(lambda x: x<5, [1,4,6,4,1]) --> 1 4

for x in iterable:

if condition(x):

yield x

else:

break

def filterfalse(condition, iterable):

# filterfalse(lambda x: x%2, range(10)) --> 0 2 4 6 8

# 相当于 lambda x: x%2 == 1 == True

if condition is None:

condition = bool

for x in iterable:

if not condition(x):

yield x

14.7.2 Create Generators Yielding Mapped Data

itertools.accumulate(Iterable data, Function f = operator.add: yield $x_1, \operatorname f(x_2, x_1), \operatorname f(x_3, \operatorname f(x_2, x_1)), \dots$ for $x_i$ indata- (built-in)

enumerate(Iterable data, start=0): yield(i+start, data[i])foriinrange(0, len(data)) - (built-in)

map(Function f, Iterable data_1, ..., Iterable data_n): yieldf(x_1, ..., x_n)for(x_1, ..., x_n)inzip(data_1, ..., data_n) itertools.starmap(Function f, Iterable data): yieldf(*i)foriindata

def accumulate(iterable, func=operator.add):

'Return running totals'

# accumulate([1,2,3,4,5]) --> 1 3 6 10 15

# accumulate([1,2,3,4,5], operator.mul) --> 1 2 6 24 120

it = iter(iterable)

try:

total = next(it)

except StopIteration:

return

yield total

for element in it:

total = func(total, element)

yield total

def starmap(function, iterable):

# starmap(pow, [(2,5), (3,2), (10,3)]) --> 32 9 1000

for args in iterable:

yield function(*args)

14.7.3 Create Generators Yielding Merged Data

itertools.chain(Iterable A, ..., Iterable Z): yield $a_1, \dots, a_{n_A}, b_1, \dots, y_{n_Y}, z_1, \dots, z_{n_Z}$itertools.chain.from_iterable(Iterable data):== itertools.chain(*data)- (built-in)

zip(Iterable A, ..., Iterable Z): 参 Python: Zip itertools.zip_longest(Iterable A, ..., Iterable Z, fillvalue=None): 你理解了zip的话看这个函数名自然就明白它的功能了

def chain(*iterables):

# chain('ABC', 'DEF') --> A B C D E F

for it in iterables:

for element in it:

yield element

def from_iterable(iterables):

# chain.from_iterable(['ABC', 'DEF']) --> A B C D E F

for it in iterables:

for element in it:

yield element

class ZipExhausted(Exception):

pass

def zip_longest(*args, **kwds):

# zip_longest('ABCD', 'xy', fillvalue='-') --> Ax By C- D-

fillvalue = kwds.get('fillvalue')

counter = len(args) - 1

def sentinel():

nonlocal counter

if not counter:

raise ZipExhausted

counter -= 1

yield fillvalue

fillers = repeat(fillvalue)

iterators = [chain(it, sentinel(), fillers) for it in args]

try:

while iterators:

yield tuple(map(next, iterators))

except ZipExhausted:

pass

14.7.4 Create Generators Yielding Repetition

itertools.count(start=0, step=1): yield $\text{start}, \text{start}+\text{step}, \text{start}+2 \cdot \text{step}, \dots$ endlesslyitertools.repeat(object x[, ntimes]): yieldxendlessly orntimestimesitertools.cycle(Iterable data): yield $x_1, \dots, x_n, x_1, \dots, x_n, x_1, \dots$ repeatedly and endlessly for $x_i$ indata

def count(start=0, step=1):

# count(10) --> 10 11 12 13 14 ...

# count(2.5, 0.5) -> 2.5 3.0 3.5 ...

n = start

while True:

yield n

n += step

def repeat(object, times=None):

# repeat(10, 3) --> 10 10 10

if times is None:

while True:

yield object

else:

for i in range(times):

yield object

def cycle(iterable):

# cycle('ABCD') --> A B C D A B C D A B C D ...

saved = []

for element in iterable:

yield element

saved.append(element)

while saved:

for element in saved:

yield element

注意这两种 repeat a list 的方式:

>>> from itertools import chain, repeat

>>> import numpy as np

>>> list(chain(*repeat([1, 2, 3], 3)))

[1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3]

>>> np.repeat([1, 2, 3], 3).tolist()

[1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3]

14.7.5 Create Generators Yielding Combinations and Permutations

itertools.product(Iterable A, ..., Iterable Z, repeat=1): yield all $(a_i, b_j, \dots, z_k)$ where $a_i \in A, b_j \in B, \dots, z_k \in Z$- 一共会 yield $(\vert A \vert \cdot \vert B \vert \cdot \ldots \cdot \vert Z \vert)^{\text{repeat}}$ 个 tuple

repeat=2的效果是 yield all $(a_{i_1}, b_{j_1}, \dots, z_{k_1}, a_{i_2}, b_{j_2}, \dots, z_{k_2})$,依此类推- 还有一种用法是

product(A, repeat=2),等价于product(A, A)

itertools.combinations(Iterable X, k): yield all $(x_{i_1}, x_{i_2}, \dots, x_{i_k})$ where $x_{i_j} \in X$ and $i_1 < i_2 < \dots < i_k$itertools.combinations_with_replacement(Iterable X, k): yield all $(x_{i_1}, x_{i_2}, \dots, x_{i_k})$ where $x_{i_j} \in X$ and $i_1 \leq i_2 \leq \dots \leq i_k$itertools.permutations(Iterable X, k): yield all $(x_{i_1}, x_{i_2}, \dots, x_{i_k})$ where $x_{i_j} \in X$ and $i_1 \neq i_2 \neq \dots \neq i_k$

>>> import itertools

>>> list(itertools.combinations([1,2,3], 2))

[(1, 2), (1, 3), (2, 3)]

>>> list(itertools.combinations_with_replacement([1,2,3], 2))

[(1, 1), (1, 2), (1, 3), (2, 2), (2, 3), (3, 3)]

>>> list(itertools.permutations([1,2,3], 2))

[(1, 2), (1, 3), (2, 1), (2, 3), (3, 1), (3, 2)]

>>> list(itertools.product([1,2,3], repeat=2))

[(1, 1), (1, 2), (1, 3), (2, 1), (2, 2), (2, 3), (3, 1), (3, 2), (3, 3)]

假设 len(list(X)) = n,那么:

combinations一共会 yield $\operatorname{C}_{n}^{k} = {n \choose k} = \frac{n!}{(n-k)!k!}$ 个 tuplecombinations_with_replacement一共会 yield $\operatorname{C}_{n+k-1}^{k} = {n+k-1 \choose k} = \frac{(n+k-1)!}{(n-1)!k!}$ 个 tuplepermutations一共会 yield $\operatorname{A}_{n}^{k} = \frac{n!}{(n-k)!}$ 个 tuple- 你可能会问 “为啥没有 permutation with replacement 操作?” which yields $n^k$ tuples

- 因为可以用

product(X, repeat=k)实现

- 因为可以用

def product(*args, repeat=1):

# product('ABCD', 'xy') --> Ax Ay Bx By Cx Cy Dx Dy

# product(range(2), repeat=3) --> 000 001 010 011 100 101 110 111

# E.g. product('ABCD', 'xy')

# pools = [('A', 'B', 'C', 'D'), ('x', 'y')]

pools = [tuple(pool) for pool in args] * repeat

result = [[]]

for pool in pools:

# When pool = ('A', 'B', 'C', 'D')

# result = [['A'], ['B'], ['C'], ['D']]

# Then pool = ('x', 'y')

# result = [['A', 'x'], ['A', 'y'], ['B', 'x'], ['B', 'y'], ['C', 'x'], ['C', 'y'], ['D', 'x'], ['D', 'y']]

# `x+[y]` 里 x 是 list of list 的元素; y 被包装成了 list。这里利用了 list extension 来实现了一个类似集合 ∪ 的效果

result = [x+[y] for x in result for y in pool]

for prod in result:

yield tuple(prod)

def combinations(iterable, r):

# combinations('ABCD', 2) --> AB AC AD BC BD CD

# combinations(range(4), 3) --> 012 013 023 123

# E.g. combinations('ABCD', 2)

# pool = [('A', 'B', 'C', 'D')]

pool = tuple(iterable)

n = len(pool) # == 4

if r > n:

return

indices = list(range(r)) # == [0, 1]

yield tuple(pool[i] for i in indices) # yield pool(0,1)

while True:

for i in reversed(range(r)): # for i in [1, 0]

# 1st round: i == 1; indices[1] == 1 != 1 + 4 - 2; break

# 2nd round: i == 1; indices[1] == 2 != 1 + 4 - 2; break

# 3rd round: i == 1; indices[1] == 3 == 1 + 4 - 2; continue

# 3rd round: i == 0; indices[0] == 0 != 0 + 4 - 2; break

# 4th round: i == 1; indices[1] == 2 != 1 + 4 - 2; break

# 5th round: i == 1; indices[1] == 3 == 1 + 4 - 2; continue

# 5th round: i == 0; indices[0] == 1 != 0 + 4 - 2; break

# 6th round: i == 1; indices[1] == 3 == 1 + 4 - 2; continue

# 6th round: i == 0; indices[0] == 2 == 1 + 4 - 2; continue

if indices[i] != i + n - r:

break

# for-else 你可以理解成 for 执行完接了一个 finally

# 然而 java 并没有 for-finally,只有 try-finally (不要 catch)

# 6th round ended

else:

return

# 1st round: i == 1; indices[1] == 2

# 2nd round: i == 1; indices[1] == 3

# 3rd round: i == 0; indices[0] == 1

# 4th round: i == 1; indices[1] == 3

# 5th round: i == 0; indices[0] == 2

indices[i] += 1

# 1st round: i == 1; for j in []

# 2nd round: i == 1; for j in []

# 3rd round: i == 0; for j in [1]

# indices[1] = indices[0] + 1 == 2

# 4th round: i == 1; for j in []

# 5th round: i == 0; for j in [1]

# indices[1] = indices[0] + 1 == 3

for j in range(i+1, r):

indices[j] = indices[j-1] + 1

# 1st round: i == 1; yield pool(0,2)

# 2nd round: i == 1; yield pool(0,3)

# 3rd round: i == 0; yield pool(1,2)

# 4th round: i == 1; yield pool(1,3)

# 5th round: i == 0; yield pool(2,3)

yield tuple(pool[i] for i in indices)

def combinations_with_replacement(iterable, r):

# combinations_with_replacement('ABC', 2) --> AA AB AC BB BC CC

pool = tuple(iterable)

n = len(pool)

if not n and r:

return

indices = [0] * r

yield tuple(pool[i] for i in indices)

while True:

for i in reversed(range(r)):

if indices[i] != n - 1:

break

else:

return

indices[i:] = [indices[i] + 1] * (r - i)

yield tuple(pool[i] for i in indices)

def permutations(iterable, r=None):

# permutations('ABCD', 2) --> AB AC AD BA BC BD CA CB CD DA DB DC

# permutations(range(3)) --> 012 021 102 120 201 210

pool = tuple(iterable)

n = len(pool)

r = n if r is None else r

if r > n:

return

indices = list(range(n))

cycles = list(range(n, n-r, -1))

yield tuple(pool[i] for i in indices[:r])

while n:

for i in reversed(range(r)):

cycles[i] -= 1

if cycles[i] == 0:

indices[i:] = indices[i+1:] + indices[i:i+1]

cycles[i] = n - i

else:

j = cycles[i]

indices[i], indices[-j] = indices[-j], indices[i]

yield tuple(pool[i] for i in indices[:r])

break

else:

return

如果允许用现有的函数,也可以这样实现:

def combinations(iterable, r):

pool = tuple(iterable)

n = len(pool)

for indices in permutations(range(n), r):

if sorted(indices) == list(indices):

yield tuple(pool[i] for i in indices)

def combinations_with_replacement(iterable, r):

pool = tuple(iterable)

n = len(pool)

for indices in product(range(n), repeat=r):

if sorted(indices) == list(indices):

yield tuple(pool[i] for i in indices)

def permutations(iterable, r=None):

pool = tuple(iterable)

n = len(pool)

r = n if r is None else r

for indices in product(range(n), repeat=r):

if len(set(indices)) == r:

yield tuple(pool[i] for i in indices)

14.7.6 Create Generators Yielding Rearranged Data

itertools.groupby(Iterable X, key=None)- If

keyisNone, setkey = lambda x: x(identity function) - If $\operatorname{key}(x_i) = \operatorname{key}(x_j) = \dots = \operatorname{key}(x_k) = \kappa$, put $x_i, x_j, \dots, x_k$ into a

itertools._grouperobject $\psi$ (which itself is also a generator). Then yield a tuple $(\kappa, \psi(x_i, x_j, \dots, x_k))$ - Yield all such tuples

- If

- (built-in)

reversed(seq): Return a reverse iterator.seqmust be an object which has a__reversed__()method- OR

- supports the sequence protocol (the

__len__()method and the__getitem__()method with integer arguments starting at 0).

itertools.tee(Iterable X, n=2): return a tuple ofnindependentiter(X)- E.g. when

n=3, return a tuple(iter(X), iter(X), iter(X))

- E.g. when

class groupby:

# [k for k, g in groupby('AAAABBBCCDAABBB')] --> A B C D A B

# [list(g) for k, g in groupby('AAAABBBCCD')] --> AAAA BBB CC D

def __init__(self, iterable, key=None):

if key is None:

key = lambda x: x

self.keyfunc = key

self.it = iter(iterable)

self.tgtkey = self.currkey = self.currvalue = object()

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

while self.currkey == self.tgtkey:

self.currvalue = next(self.it) # Exit on StopIteration

self.currkey = self.keyfunc(self.currvalue)

self.tgtkey = self.currkey

return (self.currkey, self._grouper(self.tgtkey))

def _grouper(self, tgtkey):

while self.currkey == tgtkey:

yield self.currvalue

try:

self.currvalue = next(self.it)

except StopIteration:

return

self.currkey = self.keyfunc(self.currvalue)

def tee(iterable, n=2):

it = iter(iterable)

deques = [collections.deque() for i in range(n)]

def gen(mydeque):

while True:

if not mydeque: # when the local deque is empty

try:

newval = next(it) # fetch a new value and

except StopIteration:

return

for d in deques: # load it to all the deques

d.append(newval)

yield mydeque.popleft()

return tuple(gen(d) for d in deques)

注意这个 tee 的实现:它并不是简单地返回 (iter(X), iter(X), ...)

- 首先要牢记的是,你在接收

tee返回值的时候,gen是没有执行的!因为 iteration 还没有开始。当 iteration 开始的时候,gen才开始执行- 比如

a, b, c = tee([1,2,3], 3)时,gen没有执行,只是挂到这三个变量上了而已 - 如果你来一句

list(a),那么 iteration 就开始了,gen也就开始执行了

- 比如

a, b, c = tee([1,2,3], 3)时:a -> deque([])b -> deque([])c -> deque([])

- 第一次

next(a)时:a -> deque([1]), 然后 yield1,最终a -> deque([])b -> deque([1])c -> deque([1])

- 第二次

next(a)时:a -> deque([2]), 然后 yield2,最终a -> deque([])b -> deque([1, 2])c -> deque([1, 2])

- 如果此时

next(b):a -> deque([3])b -> deque([1, 2, 3]),然后 yield1,最终b -> deque([2, 3])c -> deque([1, 2, 3])

- 可见每次某个 deque yield 一个新值,它就给其他所有的 deque 都 append 这么一个新值

14.8 New Syntax in Python 3.3: yield from

这里只介绍了最简单最直接的用法:yield from iterable 等价于 for i in iterable: yield i。所以 chain 的实现可以简写一下:

def chain(*iterables):

for it in iterables:

for i in it:

yield i

def chain(*iterables):

for it in iterables:

yield from it

Besides replacing a loop, yield from creates a channel connecting the inner generator directly to the client of the outer generator. This channel becomes really important when generators are used as coroutines and not only produce but also consume values from the client code. 我们 16 章再深入讨论。

14.9 Iterable Reducing Functions

all(Iterable X): 注意all([])是Trueany(Iterable X): 注意any([])是Falsemax(Iterable X[, key=,][default=]): return $x_i$ which maximizes $\operatorname{key}(x_i)$; ifXis empty, returndefault- May also be invoked as

max(x1, x2, ...[, key=?])

- May also be invoked as

min(Iterable X[, key=,][default=]): return $x_i$ which minimizes $\operatorname{key}(x_i)$; ifXis empty, returndefault- May also be invoked as

min(x1, x2, ...[, key=?])

- May also be invoked as

sum(Iterable X, start=0): returnssum(X) + start- Use

math.fsum()for better precision when adding floats

- Use

functools.reduce(Function f, Iterable X[, initial]- If

initialis not given:- $r_1 = \operatorname{f}(x_1, x_2)$

- $r_2 = \operatorname{f}(r_1, x_3)$

- $r_3 = \operatorname{f}(r_2, x_4)$

- 依此类推

- return $r_{n-1}$ if $\vert X \vert = n$

- If

initial = ais given:- $r_1 = \operatorname{f}(a, x_1)$

- $r_2 = \operatorname{f}(r_1, x_2)$

- $r_3 = \operatorname{f}(r_2, x_3)$

- 依此类推

- return $r_{n}$ if $\vert X \vert = n$

- If

14.10 A Closer Look at the iter Function

As we’ve seen, Python calls iter(x) when it needs to iterate over an object x.

But iter has another trick: it can be called with two arguments to create an iterator from a regular function or any callable object. In this usage, the first argument must be a callable to be invoked repeatedly (with no arguments) to yield values, and the second argument is a sentinel: a marker value which, when returned by the callable, causes the iterator to raise StopIteration instead of yielding the sentinel.

The following example shows how to use iter to roll a six-sided die until a 1 is rolled:

>>> def d6():

... return randint(1, 6)

...

>>> d6_iter = iter(d6, 1)

>>> d6_iter

<callable_iterator object at 0x00000000029BE6A0>

>>> for roll in d6_iter:

... print(roll)

...

4

3

6

3

Another useful example to read lines from a file until a blank line is found or the end of file is reached:

with open('mydata.txt') as fp:

for line in iter(fp.readline, ''):

process_line(line)

14.11 Generators as Coroutines

PEP 342 – Coroutines via Enhanced Generators was implemented in Python 2.5. This proposal added extra methods and functionality to generator objects, most notably the .send() method.

Like gtr.__next__(), gtr.send() causes the generator to advance to the next yield, but it also allows the client using the generator to send data into it: whatever argument is passed to .send() becomes the value of the corresponding yield expression inside the generator function body. In other words, .send() allows two-way data exchange between the client code and the generator–in contrast with .__next__(), which only lets the client receive data from the generator.

E.g.

>>> def double_input():

... while True:

... x = yield

... yield x * 2

...

>>> gen = double_input()

>>> next(gen)

>>> gen.send(10)

20

>>> next(gen)

>>> next(gen)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 4, in double_input

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for *: 'NoneType' and 'int'

>>> def add_inputs():

... while True:

... x = yield

... y = yield

... yield x + y

...

>>> gen = add_inputs()

>>> next(gen)

>>> gen.send(10)

>>> gen.send(20)

30

>>> gen = add_inputs()

>>> next(gen)

>>> gen.send(10)

>>> next(gen)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 5, in add_inputs

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'NoneType'

以 add_input 为例:

next(gen),驱动到第一个yield,即执行到x = yield,停住gen.send(10),相当于执行了x = 10,然后驱动到下一个yield,即y = yield,停住gen.send(20),相当于执行了y = 20,然后驱动到下一个yield,即yield x + y,输出

所以大致的 pattern 是:

.__next__()和.send()都会驱动到一下个yield,不管是 left-handyield还是 right-handyield.send(foo)替换当前的 right-handyield为foo(然后驱动到下一个 yield)- 驱动到 right-hand

yield时直接输出 - 你一个循环里有 $N$ 个

yield,就要驱动 $N$ 次,i.e. $N_{\text{next}} + N_{\text{send}} = N_{\text{yield}}$

This is such a major “enhancement” that it actually changes the nature of generators: when used in this way, they become coroutines. David Beazley–probably the most prolific writer and speaker about coroutines in the Python community — warned in a famous PyCon US 2009 tutorial:

- Generators produce data for iteration

- Coroutines are consumers of data

- To keep your brain from exploding, you don’t mix the two concepts together

- Coroutines are not related to iteration

- Note: There is a use of having

yieldproduce a value in a coroutine, but it’s not tied to iteration.-- David Beazley

“A Curious Course on Coroutines and Concurrency”

Soapbox

Semantics of Generator Versus Iterator

A generator is an iterator; an iterator is not necessarily a generator.

Proof by code:

>>> from collections import abc

>>> e = enumerate('ABC')

>>> isinstance(e, abc.Iterator)

True

>>> import types

>>> e = enumerate('ABC')

>>> isinstance(e, types.GeneratorType)

False

Chapter 15 - Context Managers and else Blocks

15.1 Do This, Then That: else Blocks Beyond if

for-else: theelseblock will run if theforloop runs to completionelsewon’t run ifforis aborted by abreakorreturn

while-else: dittotry-else: theelseblock will run if no exception is raised in thetryblock

The use of else in loops generally follows the pattern of this snippet:

for item in my_list:

if item.flavor == 'banana':

break

else:

raise ValueError('No banana flavor found!')

In Python, try-except is commonly used for control flow, and not just for error handling. There’s even an acronym/slogan for that documented in the official Python glossary:

EAFP: Easier to Ask for Forgiveness than Permission

This common Python coding style assumes the existence of valid keys or attributes and catches exceptions if the assumption proves false. This clean and fast style is characterized by the presence of many try and except statements. The technique contrasts with the LBYL style common to many other languages such as C.

EAFP 就是你很不喜欢用的 “用 try-except 去判断 object 是否具有某个性质”,比如:用 try len(obj) 去判断 obj 是否是 sequence。

The glossary then defines LBYL:

LBYL: Look Before You Leap

This coding style explicitly tests for pre-conditions before making calls or lookups. This style contrasts with the EAFP approach and is characterized by the presence of many if statements. In a multi-threaded environment, the LBYL approach can risk introducing a race condition between “the looking” and “the leaping”. For example, the code,

if key in mapping: return mapping[key]can fail if another thread removes key from mapping after the test, but before the lookup. This issue can be solved with locks or by using the EAFP approach.

15.2 Context Managers and with Blocks

The with statement was designed to simplify the “try/finally” pattern, which guarantees that some operation is performed after a block of code, even if the block is aborted because of an exception, a return or sys.exit() call. The code in the “finally” clause usually releases a critical resource or restores some previous state that was temporarily changed.

The context manager protocol consists of the __enter__ and __exit__ methods. At the start of the with, __enter__ is invoked on the context manager object. The role of the “finally” clause is played by a call to __exit__ on the context manager object at the end of the with block.

__enter__(): No argument. Easy.__exit__(exc_type, exc_value, traceback): if an exception is raised insidewith, these three arguments get the exception data. 参:

15.3 The contextlib Utilities

参 Python Documentation: 29.6. contextlib — Utilities for with-statement contexts

15.4 Use @contextlib.contextmanager

直接作用于一个 generator function gen 上,将其包装成一个 context manager (不用你自己定义 class 然后实现 context manager 的 protocol)。但是要求这个 generator function 只能 yield 一个值出来,这个 yield 的值会赋给 with gen() as g 的 g,同时 gen() 的运行停止,yield 后面的代码在 with block 结束后继续运行。

如果 gen yield 了多个值,系统会抛一个 RuntimeError: generator didn't stop。

如果 with 结束时,__exit__ 检测到了异常,__exit__ 会调用 gen.throw(exc_value) 将异常抛到 gen 的 yield 后面。

from contextlib import contextmanager

@contextmanager

def gen():

try:

yield 'Foo'

except ValueError as ve:

print(ve)

with gen() as g:

print(g)

raise ValueError('Found Foo!')

# Output:

# Foo

# Found Foo!

Soapbox

From Raymond Hettinger: What Makes Python Awesome (23:00 to 26:15):

Then–Hettinger told us–he had an insight: subroutines are the most important invention in the history of computer languages. If you have sequences of operations like

A;B;CandP;B;Q, you can factor outBin a subroutine. It’s like factoring out the filling in a sandwich: using tuna with different breads. But what if you want to factor out the bread, to make sandwiches with wheat bread, using a different filling each time? That’s what thewithstatement offers. It’s the complement of the subroutine.

Chapter 16 - Coroutines

We find two main senses for the verb “to yield” in dictionaries: to produce or to give way. Both senses apply in Python when we use the yield keyword in a generator. A line such as yield item produces a value that is received by the caller of next(...), and it also gives way, suspending the execution of the generator so that the caller may proceed until it’s ready to consume another value by invoking next() again. The caller pulls values from the generator.

A coroutine is syntactically like a generator: just a function with the yield keyword in its body. However, in a coroutine, yield usually appears on the right side of an expression (e.g., datum = yield), and it may or may not produce a value–if there is no expression after the yield keyword, the generator yields None. The coroutine may receive data from the caller, which uses .send(datum) instead of next(...) to feed the coroutine. Usually, the caller pushes values into the coroutine.

It is even possible that no data goes in or out through the yield keyword. Regardless of the flow of data, yield is a control flow device that can be used to implement cooperative multitasking: each coroutine yields control to a central scheduler so that other coroutines can be activated.

When you start thinking of yield primarily in terms of control flow, you have the mindset to understand coroutines.

16.1 How Coroutines Evolved from Generators

PEP 342 – Coroutines via Enhanced Generators added 3 methods to generators:

gen.send(x): allows the caller ofgento post dataxthat then becomes the value of theyieldexpression inside the generator function.- This allows a generator to be used as a coroutine: a procedure that collaborates with the caller, yielding and receiving values.

gen.throw(exc_type[, exc_value[, tb_obj]]): allows the caller ofgento throw an exception to be handled inside the generatorgen.close(): allows the caller ofgento terminate the generator

16.2 Basic Behavior of a Generator Used as a Coroutine

>>> def simple_coroutine():

... print("-> coroutine started")

... x = yield

... print("-> coroutine received:", x)

...

>>> coro = simple_coroutine()

>>> coro

<generator object simple_coroutine at 0x7fec75c2e410>

>>> next(coro)

-> coroutine started

>>> coro.send(11)

-> coroutine received: 11

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

StopIteration

A coroutine can be in one of 4 states, which can be detected by inspect.getgeneratorstate(coro):

'GEN_CREATED': Waiting to start execution.- This is the state of

corojust aftercoro = simple_coroutine() - You can start

corobynext(coro)orcoro.send(None)- You cannot send a non-

Nonevalue to a just-started coroutine

- You cannot send a non-

- The inital call of

next(coro)is often described as priming the coroutine

- This is the state of

'GEN_RUNNING': Currently being executed by the interpreter.- You’ll only see this state in a multithreaded application or if the generator object calls

getgeneratorstateon itself.

- You’ll only see this state in a multithreaded application or if the generator object calls

'GEN_SUSPENDED': Currently suspended at ayieldexpression.'GEN_CLOSED': Execution has completed.

A much complicated example on a generator-coroutine hybrid:

>>> def simple_coroutine2(a):

... print("-> Started: a = ", a)

... b = yield a

... print("-> After yield: a = ", a)

... print("-> After yield: b = ", b)

...

>>> coro2 = simple_coroutine2(7)

>>> next(coro2)

-> Started: a = 7

7

>>> coro2.send(14)

-> After yield: a = 7

-> After yield: b = 14

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

StopIteration

>>>

这一句 b = yield a 相当于同一个 yield 连接了一个 block:{ yield a; b = yield },send() 对 a 的值没有任何影响。

16.3 Example: Coroutine to Compute a Running Average

def averager():

total = 0.0

count = 0

average = None

while True:

term = yield average

total += term

count += 1

average = total/count

>>> coro_avg = averager()

>>> next(coro_avg)

>>> coro_avg.send(10)

10.0

>>> coro_avg.send(30)

20.0

>>> coro_avg.send(5)

15.0

16.4 Decorators for Coroutine Priming

from functools import wraps

def coroutine(func):

"""Decorator: primes `func` by advancing to first `yield`"""

@wraps(func)

def primer(*args,**kwargs):

gen = func(*args,**kwargs)

next(gen)

return gen

return primer

@coroutine

def averager():

...

Then you can skip calling next() on coro_avg:

>>> coro_avg = averager()

>>> coro_avg.send(10)

10.0

>>> coro_avg.send(30)

20.0

>>> coro_avg.send(5)

15.0

The yield from syntax we’ll see later automatically primes the coroutine called by it, making it incompatible with decorators such as @coroutine. The asyncio.coroutine decorator from the Python 3.4 standard library is designed to work with yield from so it does not prime the coroutine.

16.5 Coroutine Termination and Exception Handling

generator.throw(exc_type[, exc_value[, tb_obj]])- Causes the

yieldexpression where the generator was paused to raise the exception given. - If the exception is handled by the generator, flow advances to the next

yield, and the value yielded becomes the value of thegenerator.throwcall.generatoritself is still working, state being'GEN_SUSPENDED'

- If the exception is not handled by the generator, it propagates to the context of the caller.

generatorwill be terminated with state'GEN_CLOSED'

- Causes the

generator.close()- Causes the

yieldexpression where the generator was paused to raise aGeneratorExitexception. - No error is reported to the caller if the generator does not handle that exception or raises

StopIteration–usually by running to completion. - When receiving a

GeneratorExit, the generator must notyielda value, otherwise aRuntimeErroris raised. - If any other exception is raised by the generator, it propagates to the caller.

- Causes the

16.6 Returning a Value from a Coroutine

from collections import namedtuple

Result = namedtuple('Result', 'count average')

def averager():

total = 0.0

count = 0

average = None

while True:

term = yield

if term is None:

break

total += term

count += 1

average = total/count

return Result(count, average)

- In order to return a value, a coroutine must terminate normally; this is why we have a

breakin thewhile-loop.

>>> coro_avg = averager()

>>> next(coro_avg)

>>> coro_avg.send(10)

>>> coro_avg.send(30)

>>> coro_avg.send(6.5)

>>> coro_avg.send(None)

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

StopIteration: Result(count=3, average=15.5)

注意你不能用 result = coro_avg.send(None) 去接收 coroutine 的返回值。The value of the return expression is smuggled to the caller as an attribute, value, of the StopIteration exception. This is a bit of a hack, but it preserves the existing behavior of generator objects: raising StopIteration when exhausted. 所以正确的接收 coroutine 返回值的方式是:

>>> coro_avg = averager()

>>> next(coro_avg)

>>> coro_avg.send(10)

>>> coro_avg.send(30)

>>> coro_avg.send(6.5)

>>> try:

... coro_avg.send(None)

... except StopIteration as exc:

... result = exc.value

...

>>> result

Result(count=3, average=15.5)

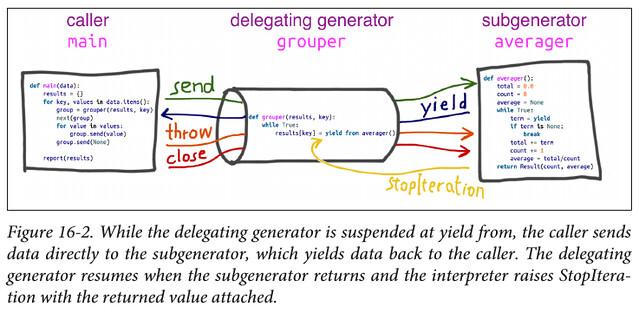

16.7 Using yield from

yield from does so much more than yield that the reuse of the keyword is arguably misleading. Similar constructs in other languages are called await, and that is a much better name because it conveys some crucial points:

- When a generator

gencallsyield from subgen(), thesubgentakes over and will yield values to the caller ofgen - The caller will in effect drive

subgendirectly - Meanwhile

genwill be blocked, waiting untilsubgenterminates

A good example of yield from is in Recipe 4.14. Flattening a Nested Sequence in Beazley and Jones’s Python Cookbook, 3E (source code available on GitHub):

# Example of flattening a nested sequence using subgenerators

from collections import Iterable

def flatten(items, ignore_types=(str, bytes)): # `ignore_types` is a good design!

for x in items:

if isinstance(x, Iterable) and not isinstance(x, ignore_types):

yield from flatten(x)

else:

yield x

items = [1, 2, [3, 4, [5, 6], 7], 8]

# Produces 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

for x in flatten(items):

print(x)

The real nature of yield from cannot be demonstrated with simple iterables; it requires the mind-expanding use of nested generators. That’s why PEP 380, which introduced yield from, is titled “Syntax for Delegating to a Subgenerator.” PEP 380 defines:

- delegating generator (delegatee): The generator function that contains the

yield from <iterable>expression. - subgenerator (delegator): The generator obtained from the

<iterable>part of theyield fromexpression. - caller (client): The client code that calls the delegating generator. (“client” might be better according to the book author)

from collections import namedtuple

Result = namedtuple('Result', 'count average')

# the subgenerator

def averager():

total = 0.0

count = 0

average = None

while True:

term = yield

if term is None:

break

total += term

count += 1

average = total/count

return Result(count, average)

# the delegating generator

def grouper(results, key):

while True:

results[key] = yield from averager()

# the client code, a.k.a. the caller

def main(data):

results = {}

for key, values in data.items():

group = grouper(results, key)

next(group)

for value in values:

group.send(value)

group.send(None) # important!

# print(results)

# uncomment to debug

report(results)

# output report

def report(results):

for key, result in sorted(results.items()):

group, unit = key.split(';')

print('{:2} {:5} averaging {:.2f}{}'.format(

result.count, group, result.average, unit))

data = {

'girls;kg': [40.9, 38.5, 44.3, 42.2, 45.2, 41.7, 44.5, 38.0, 40.6, 44.5],

'girls;m': [1.6, 1.51, 1.4, 1.3, 1.41, 1.39, 1.33, 1.46, 1.45, 1.43],

'boys;kg': [39.0, 40.8, 43.2, 40.8, 43.1, 38.6, 41.4, 40.6, 36.3],

'boys;m': [1.38, 1.5, 1.32, 1.25, 1.37, 1.48, 1.25, 1.49, 1.46],

}

main(data)

# Output:

"""

9 boys averaging 40.42kg

9 boys averaging 1.39m

10 girls averaging 42.04kg

10 girls averaging 1.43m

"""

这个例子耍了一个 trick:因为 delegator 的 yield from 默认会处理 delegatee 的 StopIteration 而 client 需要自己去 try-except delegator 的 StopIteration,所以这里 grouper 就设计成了永远不 return,也就永远不会抛 StopIteration。不这么设计的话,下面这张图的 grouper 一样要传 StopIteration 给 main。

具体的执行过程中的细节,书上并没有讲得很细,可以参考:

- Python: Yes, coroutines are complicated, but they can be used as simply as generators

- Python: Put simply, generators are special coroutines

16.8 The Meaning of yield from

关于 yield、assignment 和 return value 的逻辑,讲得基本和你总结的差不多。这里补充一下异常的情况:

- Exceptions other than

GeneratorExitthrown into the delegator are passed to thethrow()method of the delegatee. If the call raisesStopIteration, the delegator is resumed. Any other exception is propagated to the delegator. - If a

GeneratorExitis thrown into the delegator, or theclose()method of the delegator is called, then theclose()method of the delegatee is called if it has one. If this call results in an exception, it is propagated to the delegator. Otherwise,GeneratorExitis raised in the delegator.

Consider that yield from appears in a delegator. The client code drives delegator, which drives the delegatee. So, to simplify the logic involved, let’s pretend the client doesn’t ever call .throw(...) or .close() on the delegator. Let’s also pretend the delegatee never raises an exception until it terminates, when StopIteration is raised by the interpreter. Then a simplified version of pseudocode explaining RESULT = yield from EXPR is:

_i = iter(EXPR) # Coroutines are also generators and `iter(coro) == coro`

try:

_y = next(_i)

except StopIteration as _e:

_r = _e.value

else:

while 1:

_s = yield _y # Delegator receives a value from client

try:

_y = _i.send(_s) # Delegator re-sends this value to its delegatee

except StopIteration as _e:

_r = _e.value

break

RESULT = _r

In this simplified pseudocode, the variable names used in the pseudocode published in PEP 380 are preserved. The variables are:

_i(iterator): The delegetee_y(yielded): A value yielded from the delegetee_r(result): The eventual result (i.e., the value of the yield from expression when the delegatee ends)_s(sent): A value sent by the caller to the delegating generator, which is forwarded to the delegatee_e(exception): An exception (always an instance ofStopIterationin this simplified pseudocode)

The full explanation in PEP 380 – Syntax for Delegating to a Subgenerator: Formal Semantics is:

"""

1. The statement

`RESULT = yield from EXPR`

is semantically equivalent to

"""

_i = iter(EXPR)

try:

_y = next(_i)

except StopIteration as _e:

_r = _e.value

else:

while 1:

try:

_s = yield _y

except GeneratorExit as _e:

try:

_m = _i.close

except AttributeError:

pass

else:

_m()

raise _e

except BaseException as _e:

_x = sys.exc_info()

try:

_m = _i.throw

except AttributeError:

raise _e

else:

try:

_y = _m(*_x)

except StopIteration as _e:

_r = _e.value

break

else:

try:

if _s is None:

_y = next(_i)

else:

_y = _i.send(_s)

except StopIteration as _e:

_r = _e.value

break

RESULT = _r

"""

2. In a generator, the statement

`return value`

is semantically equivalent to

`raise StopIteration(value)`

except that, as currently, the exception cannot be caught by except clauses within the returning generator.

"""

"""

3. The StopIteration exception behaves as though defined thusly:

"""

class StopIteration(Exception):

def __init__(self, *args):

if len(args) > 0:

self.value = args[0]

else:

self.value = None

Exception.__init__(self, *args)

You’re not meant to learn about it by reading the expansion—that’s only there to pin down all the details for language lawyers.

16.9 Use Case: Coroutines for Discrete Event Simulation

Coroutines are a natural way of expressing many algorithms, such as simulations, games, asynchronous I/O, and other forms of event-driven programming or co-operative multitasking.

-- Guido van Rossum and Phillip J. Eby

PEP 342—Coroutines via Enhanced Generators

Coroutines are the fundamental building block of the asyncio package. A simulation shows how to implement concurrent activities using coroutines instead of threads–and this will greatly help when we tackle asyncio with in Chapter 18.

16.9.1 Discrete Event Simulations

A discrete event simulation (DES) is a type of simulation where a system is modeled as a sequence of events. In a DES, the simulation “clock” does not advance by fixed increments, but advances directly to the simulated time of the next modeled event. For example, if we are simulating the operation of a taxi cab from a high-level perspective, one event is picking up a passenger, the next is dropping the passenger off. It doesn’t matter if a trip takes 5 or 50 minutes: when the drop off event happens, the clock is updated to the end time of the trip in a single operation. In a DES, we can simulate a year of cab trips in less than a second. This is in contrast to a continuous simulation where the clock advances continuously by a fixed — and usually small — increment.

Intuitively, turn-based games are examples of DESs: the state of the game only changes when a player moves, and while a player is deciding the next move, the simulation clock is frozen. Real-time games, on the other hand, are continuous simulations where the simulation clock is running all the time, the state of the game is updated many times per second, and slow players are at a real disadvantage.

16.9.2 The Taxi Fleet Simulation

In our simulation program, taxi_sim.py, a number of taxi cabs are created. Each will make a fixed number of trips and then go home. A taxi leaves the garage and starts “prowling”–looking for a passenger. This lasts until a passenger is picked up, and a trip starts. When the passenger is dropped off, the taxi goes back to prowling.

The time elapsed during prowls and trips is generated using an exponential distribution.

# In an Event instance,

# time is the simulation time when the event will occur (in minute),

# proc is the identifier of the taxi process instance, and

# action is a string describing the activity.

Event = collections.namedtuple('Event', 'time proc action')

def taxi_process(ident, trips, start_time=0):

"""Yield to simulator issuing event at each state change"""

time = yield Event(start_time, ident, 'leave garage')

for i in range(trips):

time = yield Event(time, ident, 'pick up passenger')

time = yield Event(time, ident, 'drop off passenger')

yield Event(time, ident, 'going home')

# end of taxi process

>>> from taxi_sim import taxi_process

>>> taxi = taxi_process(ident=13, trips=2, start_time=0)

>>> next(taxi)

Event(time=0, proc=13, action='leave garage')

>>> taxi.send(_.time + 7) # In the console, the `_` variable is bound to the last result

Event(time=7, proc=13, action='pick up passenger')

>>> taxi.send(_.time + 23)

Event(time=30, proc=13, action='drop off passenger')

>>> taxi.send(_.time + 5)

Event(time=35, proc=13, action='pick up passenger')

>>> taxi.send(_.time + 48)

Event(time=83, proc=13, action='drop off passenger')

>>> taxi.send(_.time + 1)

Event(time=84, proc=13, action='going home')

>>> taxi.send(_.time + 10)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

StopIteration

To instantiate the Simulator class, the main function of taxi_sim.py builds a taxis dictionary like this:

# DEPARTURE_INTERVAL == 5

taxis = {i: taxi_process(ident=i, trips=(i + 1) * 2, start_time=i * DEPARTURE_INTERVAL) for i in range(num_taxis)}

"""

If num_taxis = 3

taxis = {0: taxi_process(ident=0, trips=2, start_time=0),

1: taxi_process(ident=1, trips=4, start_time=5),

2: taxi_process(ident=2, trips=6, start_time=10)}

"""

Priority queues are a fundamental building block of discrete event simulations: events are created in any order, placed in the queue, and later retrieved in order according to the scheduled time of each one. For example, the first two events placed in the queue may be:

Event(time=14, proc=0, action='pick up passenger') # taxi 0 (start_time=0) would take 14 minutes to pick up his first passenger

Event(time=11, proc=1, action='pick up passenger') # taxi 1 (start_time=10) would take 1 minute to pick up his first passenger

The second event holds higher priority because of shorter prowling time.

Code for Simulator class is:

class Simulator:

def __init__(self, procs_map):

self.events = queue.PriorityQueue()

self.procs = dict(procs_map)

def run(self, end_time):

"""Schedule and display events until time is up"""

# schedule the first event for each cab

for _, proc in sorted(self.procs.items()):

first_event = next(proc) # yield 'leave garage' Event

self.events.put(first_event)

# main loop of the simulation

sim_time = 0

while sim_time < end_time:

if self.events.empty():

print('*** end of events ***')

break

current_event = self.events.get()

sim_time, proc_id, previous_action = current_event

print('taxi:', proc_id, proc_id * ' ', current_event)

active_proc = self.procs[proc_id]

next_time = sim_time + compute_duration(previous_action) # Duaration is fixed for a given type of actions

try:

next_event = active_proc.send(next_time)

except StopIteration:

del self.procs[proc_id]

else:

self.events.put(next_event) # Enqueue the next Event

else:

msg = '*** end of simulation time: {} events pending ***'

print(msg.format(self.events.qsize()))

sim = Simulator(taxis)

sim.run(end_time)

Chapter 17 - Concurrency with Futures

This chapter focuses on the concurrent.futures library introduced in Python 3.2, but also available for Python 2.5 and newer as the futures package on PyPI.

Here I also introduce the concept of futures–objects representing the asynchronous execution of an operation.

17.1 Example: Web Downloads in Three Styles

To handle network I/O efficiently, you need concurrency, as it involves high latency–so instead of wasting CPU cycles waiting, it’s better to do something else until a response comes back from the network.

Three scripts will be shown below to download images of 20 country flags:

flags.py: runs sequentially. Only requests the next image when the previous one is downloaded and saved to diskflags_threadpool.py: requests all images practically at the same time. Usesconcurrent.futurespackageflags_asyncio.py: ditto. Usesasynciopackage

17.1.1 Style I: Sequential

import os

import time

import sys

import requests

POP20_CC = ('CN IN US ID BR PK NG BD RU JP '

'MX PH VN ET EG DE IR TR CD FR').split()

BASE_URL = 'http://flupy.org/data/flags'

DEST_DIR = './'

def save_flag(img, filename):

path = os.path.join(DEST_DIR, filename)

with open(path, 'wb') as fp:

fp.write(img)

def get_flag(cc):

url = '{}/{cc}/{cc}.gif'.format(BASE_URL, cc=cc.lower())

resp = requests.get(url)

return resp.content

def show(text):

print(text, end=' ')

sys.stdout.flush()

def download_many(cc_list):

for cc in sorted(cc_list):

image = get_flag(cc)

show(cc)

save_flag(image, cc.lower() + '.gif')

return len(cc_list)

def main(download_many):

t0 = time.time()

count = download_many(POP20_CC)

elapsed = time.time() - t0

msg = '\n{} flags downloaded in {:.2f}s'

print(msg.format(count, elapsed))

main(download_many)

The requests library by Kenneth Reitz is available on PyPI and is more powerful and easier to use than the urllib.request module from the Python 3 standard library. In fact, requests is considered a model Pythonic API. It is also compatible with Python 2.6 and up, while the urllib2 from Python 2 was moved and renamed in Python 3, so it’s more convenient to use requests regardless of the Python version you’re targeting.

17.1.2 Style II: Concurrent with concurrent.features

from concurrent import futures

from flags import save_flag, get_flag, show, main

MAX_WORKERS = 20

def download_one(cc):

image = get_flag(cc)

show(cc)

save_flag(image, cc.lower() + '.gif')

return cc

def download_many(cc_list):

workers = min(MAX_WORKERS, len(cc_list))

"""

The `executor.__exit__` method will call `executor.shutdown(wait=True)`,

which will block until all threads are done.

"""

with futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(workers) as executor:

res = executor.map(download_one, sorted(cc_list))

return len(list(res))

main(download_many)

This is a common refactoring when writing concurrent code: turning the body of a sequential for loop into a function to be called concurrently.

17.1.3 Style III: Concurrent with asyncio

import asyncio

import aiohttp

from flags import BASE_URL, save_flag, show, main

@asyncio.coroutine

def get_flag(cc):

url = '{}/{cc}/{cc}.gif'.format(BASE_URL, cc=cc.lower())

resp = yield from aiohttp.request('GET', url)

image = yield from resp.read()

return image

@asyncio.coroutine

def download_one(cc):

image = yield from get_flag(cc)

show(cc)

save_flag(image, cc.lower() + '.gif')

return cc

def download_many(cc_list):

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

to_do = [download_one(cc) for cc in sorted(cc_list)]

wait_coro = asyncio.wait(to_do)

res, _ = loop.run_until_complete(wait_coro)

loop.close()

return len(res)

main(download_many)

Will cover it in next chapter.

17.1.4 What Are the Futures?

As of Python 3.4, there are two classes named Future in the standard library: concurrent.futures.Future and asyncio.Future. They serve the same purpose: an instance of either Future class represents a deferred computation that may or may not have completed. This is similar to the Deferred class in Twisted, the Future class in Tornado, and Promise objects in various JavaScript libraries.

Futures encapsulate pending operations so that they can be put in queues, their state of completion can be queried, and their results (or exceptions) can be retrieved when available.

- Client code should not create

Futureinstances: they are meant to be instantiated exclusively by the concurrency framework, be itconcurrent.futuresorasyncio. - Client code is not supposed to change the state of a future.

Future.done(): nonblocking and returns a bool to tell you whether the callable linked to this future has executed or notFuture.add_done_callback(func): Instead of asking whether a future is done, client code usually asks to be notified. If you addfuncas a done-callback to futuref,func(f)will be invoked whenfis done.Future.result(): returns the result of the callable linked to this future- In

concurrent.futures, callingf.result()will block the caller’s thread until the result is ready- You can also set a

timeoutargument to raise aTimeErroriffis not done within the specified time

- You can also set a

- In

asyncio,f.result()is non-blocking and the preferred way to get the result of futures is to useyield from–which doesn’t work withconcurrency.futures.Futureinstances.- No such

timeoutargument

- No such

- In

To get a practical look at futures, we can rewrite last example:

def download_many(cc_list):

cc_list = cc_list[:5]

with futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=3) as executor:

to_do = []

for cc in sorted(cc_list):

future = executor.submit(download_one, cc)

to_do.append(future)

msg = 'Scheduled for {}: {}'

print(msg.format(cc, future))

"""

`as_completed` function takes an iterable of futures and

returns an iterator that yields futures as they are done.

"""

results = []

for future in futures.as_completed(to_do):

res = future.result()

msg = '{} result: {!r}'

print(msg.format(future, res))

results.append(res)

return len(results)

Strictly speaking, none of the concurrent scripts we tested so far can perform downloads in parallel. The concurrent.futures examples are limited by the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), and the flags_asyncio.py is single-threaded.

17.2 Blocking I/O and the GIL

参 Python GIL: Global Interpreter Lock

When we write Python code, we have no control over the GIL, but a built-in function or an extension written in C can release the GIL while running time-consuming tasks. In fact, a Python library coded in C can manage the GIL, launch its own OS threads, and take advantage of all available CPU cores. This complicates the code of the library considerably, and most library authors don’t do it.

However, all standard library functions that perform blocking I/O release the GIL when waiting for a result from the OS. This means Python programs that are I/O bound can benefit from using threads at the Python level: while one Python thread is waiting for a response from the network, the blocked I/O function releases the GIL so another thread can run.

17.3 Launching Processes with concurrent.futures

The package enables truly parallel computations because it can distribute work among multiple Python processes (using the ProcessPoolExecutor class)–thus bypassing the GIL and leveraging all available CPU cores, if you need to do CPU-bound processing.

def download_many(cc_list):

workers = min(MAX_WORKERS, len(cc_list))

with futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(workers) as executor:

def download_many(cc_list):

with futures.ProcessPoolExecutor() as executor:

There is an optional argument in ProcessPoolExecutor constructor, but most of the time we don’t use it–the default is the number of CPUs returned by os.cpu_count(). This makes sense: for CPU-bound processing, it makes no sense to ask for more workers than CPUs.

There is no advantage in using a ProcessPoolExecutor for the flags download example or any I/O-bound job.

17.4 Experimenting with executor.map

The simplest way to run several callables concurrently is with the executor.map function.

from time import sleep, strftime

from concurrent import futures

def display(*args):

print(strftime('[%H:%M:%S]'), end=' ')

print(*args)

def loiter(n):

msg = '{}loiter({}): doing nothing for {}s...'

display(msg.format('\t'*n, n, n))

sleep(n)

msg = '{}loiter({}): done.'

display(msg.format('\t'*n, n))

return n * 10

def main():

display('Script starting.')

executor = futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=3)

results = executor.map(loiter, range(5))

display('results:', results)

display('Waiting for individual results:')

for i, result in enumerate(results): # Note here

display('result {}: {}'.format(i, result))

main()

The enumerate call in the for loop will implicitly invoke next(results), which in turn will invoke _f.result() on the (internal) _f future representing the first call, loiter(0). The result method will block until the future is done, therefore each iteration in this loop will have to wait for the next result to be ready.

The executor.map function is easy to use but it has a feature that may or may not be helpful, depending on your needs: it returns the results exactly in the same order as the calls are started: if the first call takes 10s to produce a result, and the others take 1s each, your code will block for 10s as it tries to retrieve the first result of the generator returned by map. After that, you’ll get the remaining results without blocking because they will be done. That’s OK when you must have all the results before proceeding, but often it’s preferable to get the results as they are ready, regardless of the order they were submitted. To do that, you need a combination of the executor.submit method and the futures.as_completed function.

The combination of executor.submit and futures.as_completed is more flexible than executor.map because you can submit different callables and arguments, while executor.map is designed to run the same callable on the different arguments. In addition, the set of futures you pass to futures.as_completed may come from more than one executor–perhaps some were created by a ThreadPoolExecutor instance while others are from a ProcessPoolExecutor.

17.5 Downloads with Progress Display and Error Handling

一个完整的例子,用到了 tqdm,需要架设 Mozilla Vaurien,略。

17.5.3 threading and multiprocessing

threading 和 multiprocessing 都是底层 module,concurrent.features 可以看做是 multiprocessing 的包装,提供了简单的接口,屏蔽了底层技术细节

Chapter 18 - Concurrency with asyncio

Concurrency is about dealing with lots of things at once.

Parallelism is about doing lots of things at once.

Not the same, but related.

One is about structure, one is about execution.

Concurrency provides a way to structure a solution to solve a problem that may (but not necessarily) be parallelizable.

-- Rob Pike

This chapter introduces asyncio, a package that implements concurrency with corou‐ tines driven by an event loop.

Because it uses yield from expressions extensively, asyncio is incompatible with older versions before Python 3.3.

18.1 Thread Versus Coroutine: A Comparison

Here we introduce a fun example to display an animated spinner made with the ASCII characters |/-\ on the console while some long computation is running.

import threading

import itertools

import time

import sys

class Signal:

go = True

def spin(msg, signal):

write, flush = sys.stdout.write, sys.stdout.flush

for char in itertools.cycle('|/-\\'):

status = char + ' ' + msg

write(status)

flush()

write('\x08' * len(status))

time.sleep(.1)

if not signal.go:

break

write(' ' * len(status) + '\x08' * len(status))

def slow_function():

# pretend waiting a long time for I/O

time.sleep(3) # Calling `sleep` would block the `main` thread, but GIL will be released to `spin` thread

return 42

def supervisor():

signal = Signal()

spinner = threading.Thread(target=spin, args=('thinking!', signal))

print('spinner object:', spinner)

spinner.start()

result = slow_function()

signal.go = False

spinner.join()

return result

def main():

result = supervisor()

print('Answer:', result)

main()

Note that, by design, there is no API for terminating a thread in Python. You must send it a message to shut down.

Now let’s see how the same behavior can be achieved with an @asyncio.coroutine instead of a thread.

import asyncio

import itertools

import sys

@asyncio.coroutine # ①

def spin(msg):

write, flush = sys.stdout.write, sys.stdout.flush

for char in itertools.cycle('|/-\\'):

status = char + ' ' + msg

write(status)

flush()

write('\x08' * len(status))

try:

yield from asyncio.sleep(.1) # ②

except asyncio.CancelledError:

break

write(' ' * len(status) + '\x08' * len(status))

@asyncio.coroutine

def slow_function():

# pretend waiting a long time for I/O

yield from asyncio.sleep(3)

return 42

@asyncio.coroutine # ③

def supervisor():

spinner = asyncio.async(spin('thinking!')) # ④

print('spinner object:', spinner)

result = yield from slow_function() # ⑤

spinner.cancel() # ⑥

return result

def main():

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

result = loop.run_until_complete(supervisor()) # ⑦

loop.close()

print('Answer:', result)

main()

- ① Coroutines intended for use with

asyncioshould be decorated with@asyn cio.coroutine. This not mandatory, but is highly advisable.- It makes the coroutines stand out among regular functions, and helps with debugging by issuing a warning when a coroutine is garbage collected without being yielded from–which means some operation was left unfinished and is likely a bug.

- This is not a priming decorator.

- ② Use

yield from asyncio.sleep(.1)instead of justtime.sleep(.1), to sleep without blocking the event loop.- Never use

time.sleep(...)inasynciocoroutines unless you want to block the main thread, therefore freezing the event loop and probably the whole application as well. - If a coroutine needs to spend some time doing nothing, it should

yield from asyn cio.sleep(DELAY).

- Never use

- ③

supervisoris now a coroutine as well, so it can driveslow_functionwithyield from. - ④

asyncio.async(...)schedules thespincoroutine to run, wrapping it in aTaskobject, which is returned immediately. - ⑤ Drive the

slow_function(). When that is done, get the returned value. Meanwhile, the event loop will continue running becauseslow_functionultimately usesyield from asyncio.sleep(3)to hand control back to the main loop. - ⑥ A

Taskobject can be cancelled; this raisesasyncio.CancelledErrorat theyieldline where the coroutine is currently suspended. - ⑦ Drive the

supervisorcoroutine to completion; the return value of the coroutine is the return value of this call.- Just imagine that

loop.run_until_completeis callingnext()or.send()onsupervisor()

- Just imagine that

Here is a summary of the main differences to note between the two supervisor implementations:

- An

asyncio.Taskis roughly the equivalent of athreading.Thread. - A

Taskdrives a coroutine, and aThreadinvokes a callable. - You don’t instantiate

Taskobjects yourself, you get them by passing a coroutine toasyncio.async(...)orloop.create_task(...). - When you get a

Taskobject, it is already scheduled to run (e.g., byasyn cio.async); aThreadinstance must be explicitly told to run by calling itsstartmethod.

18.1.1 asyncio.Future: Nonblocking by Design

In asyncio, BaseEventLoop.create_task(...) takes a coroutine, schedules it to run, and returns an asyncio.Task instance–which is also an instance of asyncio.Future because Task is a subclass of Future designed to wrap a coroutine. This is analogous to how we create concurrent.futures.Future instances by invoking Executor.submit(...).

In asyncio.Future, the .result() method takes no arguments, so you can’t specify a timeout. Also, if you call .result() and the future is not done, it does not block waiting for the result. Instead, an asyncio.InvalidStateError is raised.

However, the usual way to get the result of an asyncio.Future is to yield from it, which automatically takes care of waiting for it to finish, without blocking the event loop–because in asyncio, yield from is used to give control back to the event loop.

Note that using yield from with a future is the coroutine equivalent of the functionality offered by add_done_callback: instead of triggering a callback, when the delayed operation is done, the event loop sets the result of the future, and the yield from expression produces a return value inside our suspended coroutine, allowing it to resume.

So basically you won’t call my_future.result() nor my_future.add_done_callback(...) with asyncio.Future.

18.1.2 Yielding from Futures, Tasks, and Coroutines

In asyncio, there is a close relationship between futures and coroutines because you can get the result of an asyncio.Future by yielding from it. This means that res = yield from foo() works

- if

foois a coroutine function, or - if

foois a plain function that returns aFutureorTaskinstance.

In order to execute, a coroutine must be scheduled, and then it’s wrapped in an asyncio.Task. Given a coroutine, there are two main ways of obtaining a Task:

asyncio.async(coro_or_future, *, loop=None)- If

coro_or_futureis aFutureorTask,coro_or_futurewill be returned unchanged. - If

coro_or_futureis a coroutine,loop.create_task(...)will be called on it to create aTask- If

loopis not passed in,loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

- If

- If

BaseEventLoop.create_task(coro)

Several asyncio functions accept coroutines and wrap them in asyncio.Task objects automatically, using asyncio.async internally. One example is BaseEventLoop.run_until_complete(...).

18.2 Downloading with asyncio and aiohttp

Previously we used requests library, which performs blocking I/O. To leverage asyncio, we must replace every function that hits the network with an asynchronous version that is invoked with yield from. And that’s why we use aiohttp here.

import asyncio

import aiohttp

from flags import BASE_URL, save_flag, show, main

@asyncio.coroutine

def get_flag(cc):

url = '{}/{cc}/{cc}.gif'.format(BASE_URL, cc=cc.lower())

resp = yield from aiohttp.request('GET', url)

image = yield from resp.read()

return image

@asyncio.coroutine

def download_one(cc):

image = yield from get_flag(cc)

show(cc)

save_flag(image, cc.lower() + '.gif') # ①

return cc

def download_many(cc_list):

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

to_do = [download_one(cc) for cc in sorted(cc_list)]

wait_coro = asyncio.wait(to_do) # ②

res, _ = loop.run_until_complete(wait_coro) # ③

loop.close()

return len(res)

main(download_many)

- ① For maximum performance, the

save_flagoperation should be asynchronous, butasynciodoes not provide an asynchronous filesystem API at this time. - ② Despite its name,

waitis not a blocking function. It’s a coroutine that completes when all the coroutines passed to it are done. - ③ To drive the coroutine created by

wait, we pass it toloop.run_until_complete(...)- When

wait_corocompletes, it returns a tuple where the first item is the set of completed futures and the second is the set of those not completed.

- When

There are a lot of new concepts to grasp in asyncio but the overall logic is easy to follow if you employ a trick suggested by Guido van Rossum himself: squint (look at someone or something with one or both eyes partly closed in an attempt to see more clearly or as a reaction to strong light) and pretend the yield from keywords are not there. If you do that, you’ll notice that the code is as easy to read as plain old sequential code.

Using the yield from foo syntax avoids blocking because the current coroutine is suspended, but the control flow goes back to the event loop, which can drive other coroutines. When the foo future or coroutine is done, it returns a result to the suspended coroutine, resuming it.

18.3 Running Circling Around Blocking Calls

There are two ways to prevent blocking calls to halt the progress of the entire application:

- Run each blocking operation in a separate thread.

- Turn every blocking operation into a nonblocking asynchronous call.

There is a memory overhead for each suspended coroutine, but it’s orders of magnitude smaller than the overhead for each thread.

18.4 Enhancing the asyncio downloader Script

18.4.1 Using asyncio.as_completed

import asyncio

import collections

import aiohttp

from aiohttp import web

import tqdm

from flags2_common import main, HTTPStatus, Result, save_flag

# default set low to avoid errors from remote site, such as

# 503 - Service Temporarily Unavailable

DEFAULT_CONCUR_REQ = 5

MAX_CONCUR_REQ = 1000

class FetchError(Exception):

def __init__(self, country_code):

self.country_code = country_code

@asyncio.coroutine

def get_flag(base_url, cc):

url = '{}/{cc}/{cc}.gif'.format(base_url, cc=cc.lower())

resp = yield from aiohttp.request('GET', url)

if resp.status == 200:

image = yield from resp.read()

return image

elif resp.status == 404:

raise web.HTTPNotFound()

else:

raise aiohttp.HttpProcessingError( code=resp.status, message=resp.reason, headers=resp.headers)

@asyncio.coroutine

def download_one(cc, base_url, semaphore, verbose):

try:

with (yield from semaphore): # ①

image = yield from get_flag(base_url, cc) # ②

except web.HTTPNotFound:

status = HTTPStatus.not_found

msg = 'not found'

except Exception as exc:

raise FetchError(cc) from exc

else:

save_flag(image, cc.lower() + '.gif')

status = HTTPStatus.ok

msg = 'OK'

if verbose and msg:

print(cc, msg)

return Result(status, cc)

@asyncio.coroutine

def downloader_coro(cc_list, base_url, verbose, concur_req):

counter = collections.Counter() # ③

semaphore = asyncio.Semaphore(concur_req)

to_do = [download_one(cc, base_url, semaphore, verbose) for cc in sorted(cc_list)]

to_do_iter = asyncio.as_completed(to_do) # ④

if not verbose:

to_do_iter = tqdm.tqdm(to_do_iter, total=len(cc_list)) # ⑤

for future in to_do_iter: # ⑥

try:

res = yield from future # ⑦

except FetchError as exc:

country_code = exc.country_code

try:

error_msg = exc.__cause__.args[0]

except IndexError:

error_msg = exc.__cause__.__class__.__name__

if verbose and error_msg:

msg = '*** Error for {}: {}'

print(msg.format(country_code, error_msg))

status = HTTPStatus.error

else:

status = res.status

counter[status] += 1

return counter

def download_many(cc_list, base_url, verbose, concur_req):

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

coro = downloader_coro(cc_list, base_url, verbose, concur_req)

counts = loop.run_until_complete(coro)

loop.close()

return counts

main(download_many, DEFAULT_CONCUR_REQ, MAX_CONCUR_REQ)

- ① A

semaphoreis used as a context manager in ayield fromexpression so that the system as whole is not blocked: only this coroutine is blocked while thesemaphorecounter is at the maximum allowed number.- A

semaphoreis an object that holds an internal counter that is decremented whenever we call the.acquire()coroutine method on it, and incremented when we call the.release()coroutine method. - Calling

.acquire()does not block when the counter is greater than 0, but if the counter is 0,.acquire()will block the calling coroutine until some other coroutine calls.release()on the samesemaphore, thus incrementing the counter.

- A

- ② When this

withstatement exits, thesemaphorecounter is increased, unblocking some other coroutine instance that may be waiting for the samesemaphoreobject.- Network client code of the sort we are studying should always use some throttling mechanism to avoid pounding the server with too many concurrent requests–the overall performance of the system may degrade if the server is overloaded.

- ③ A

Counteris adictsubclass for counting hashable objects, e.g.Counter('AAABB') == Counter({'A': 3, 'B': 2}) - ④

asyncio.as_completedtakes a list of coroutines and returns an iterator that yields the coroutines in the order in which they are completed, so that when you iterate on it, you get each result as soon as it’s available. - ⑤ 这里用

tqdm包一下是为了给 ⑥ 的时候显示一下进度 - ⑥ Iterate over the completed futures

- ⑦

as_completedrequires you to loop over the returned completed futures and yield from each one of them to retrieve the result instead of callingfuture.result().

18.4.2 Using an Executor to Avoid Blocking the Event Loop

In the Python community, we tend to overlook the fact that local filesystem access is blocking, rationalizing that it doesn’t suffer from the higher latency of network access.

Recall that save_flag performs disk I/O and in flags2_asyncio.py, it blocks the single thread our code shares with the asyncio event loop. Therefore the whole application freezes while the file is being saved. The solution to this problem is the run_in_executor method of the event loop object.

Behind the scenes, the asyncio event loop has a thread pool executor, and you can send callables to be executed by it with run_in_executor.

@asyncio.coroutine

def download_one(cc, base_url, semaphore, verbose):

try:

with (yield from semaphore):