Digest of Fluent Python

Part I - Prologue

Chapter 1 - The Python Data Model

This chapter focus on special methods, i.e. dunder methods.

| code | interpreted as | comment | |

|---|---|---|---|

f = Foo(args) |

f = Foo.__new__(args).__init__(args) |

||

obj[key] |

obj.__getitem__(key) |

||

obj.foo / getattr(obj, "foo") |

obj.__getattribute__("foo") |

||

len(obj) |

obj.__len__(key) |

||

if x in obj: |

if obj.__contains__(x): |

If __contains__() is not available, Python will scan with __getitem__(). |

|

for x in obj: |

iterator = obj.__iter__() is implicitly called at the start of loops; x = iterator.__next__() is the next value and is implicitly called at each loop increment. |

If neither is available, Python will scan with __getitem__(). |

|

o1 + o2 |

o1.__add__(o2) |

||

o1 += o2 |

o1.__iadd__(o2) |

“in-place addition”. If __iadd__() is not implemented, += falls back to calling __add__() |

|

abs(obj) |

obj.__abs__() |

||

obj * 3 |

obj.__mul__(3) |

||

if obj: |

if obj.__bool__(): |

If __bool__() is not implemented, Python tries to invoke __len__(), and if $>0$, returns False. Otherwise True. |

|

repr(obj) |

obj.__rper__() |

"%s" % obj will call repr(obj). |

|

str(obj) |

obj.__str__() |

print(obj), "%s" % obj and "{}".format(obj) will call str(obj); if __str__ is not available, will fall back to __repr__(). |

__new__(cls, arg) / __init__(self, arg)

We often refer to __init__ as the constructor method, but that’s because we adopted jargon from other languages. The special method that actually constructs an instance is __new__:

- it’s a class method (but gets special treatment, so the

@classmethoddecorator is not used), and - it must return an instance

The construction workflow is like:

- If

__new__()returns an instance ofcls$\Rightarrow$- that instance will in turn be passed as the first argument

selfto__init__ - other arguments as passed as-is to

__init__

- that instance will in turn be passed as the first argument

- Otherwise $\Rightarrow$ the new instance’s

__init__()will not be invoked

# pseudo-code for object construction

def new_object(cls, *args):

self = cls.__new__(*args)

if isinstance(self, cls):

cls.__init__(self, *args)

return self

# the following statements are roughly equivalent

x = Foo('bar')

x = new_object(Foo, 'bar')

__new__() is intended mainly to allow subclasses of immutable types (like int, str, or tuple) to customize instance creation. It is also commonly overridden in custom metaclasses in order to customize class creation.

__getitem__()

We say “__getitem__ method delegates to [] operator”. And once the delegation is implemented, slicing, if-in boolean operation, for-in iteration, and random.choice() on the object is automatically supported.

from random import choice

class MyList:

def __init__(self, *args):

self.inner_list = list(args)

def __len__(self):

print("__len__ is being called...")

return len(self.inner_list)

def __getitem__(self, position):

print("__getitem__ at position {}...".format(position))

return self.inner_list[position]

if __name__ == '__main__':

ml = MyList(50, 60, 70, 80)

print(len(ml)) # 4

print(ml[0]) # 50

print(ml[-1]) # 80

print(ml[0:2]) # [50, 60]

for i in ml:

print i

print(40 in ml) # False

print(choice(ml)) # randomly pick an element

__getattribute__() / __getattr__() / getattr()

obj[key] == obj.__getitem__(key)obj.foo == obj.__getattribute__("foo")(Note the quote marks)

__getattr__() does not delegates to . operator for attribute accessing, but is called when an attribute lookup FAILS (What a misleading function name!).

getattr() is a built-in function, whose logic is like:

def getattr(obj, name[, default]):

try:

return obj.__getattribute__(name)

except AttributeError as ae:

if default is passed:

return default

else:

raise ae

Of course you can implement a similar mechanism of default values in __getattr__(), e.g. for all obj.xxx where xxx is not an attribute of obj, log this call.

Note that attributes can be functions, so it is possible to write getattr(obj, func_name)(param).

You may not want to override __getattribute__() yourself but if you somehow got a chance, pay attention to possible infinite loops caused by any form of self.xxx inside the implementation of __getattribute__(). Instead use base class method with the same name to access xxx, for example, object.__getattribute__(self, "xxx"). E.g.:

class C(object):

def __init__(self):

self.x = 100

def __getattribute__(self, name):

# Wrong! AttributeError

# return self.__dict__[name]

# OK! Calling base class's __getattribute__()

return object.__getattribute__(self, name)

# OK! Calling C's overridden version of __getattribute__()

# return super().__getattribute__(name)

__iter__() and __next__()

You can treat your own object as an iterator, so obj.__iter__() can return self and a __next__() implementation can be put inside your own object.

__repr__() vs __str__()

The string returned by __repr__() should be unambiguous and, if possible, match the source code necessary to re-create the object being represented. I.e. if possible, we would have

b = eval(repr(a))

assert a == b

A recommended way of implementing __repr__ is to return a string of a constructor call:

class BetterClass(object):

def __init__(self, x, y):

...

def __repr__(self):

return "BetterClass(%d, %d)" % (self.x, self.y)

__str__() should return a string suitable for display to end users.

If you only implement one of these special methods, choose __repr__(), because when no custom __str__() is available, Python will call __repr__() as a fallback.

Part II - Data Structures

Chapter 2 - An array of Sequences

2.1 Overview of Built-In Sequences

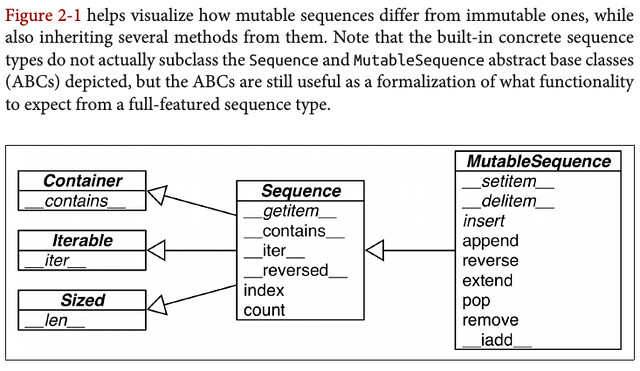

Python inherited from ABC the uniform handling of sequences. Strings, lists, byte sequences, arrays, XML elements, and database results share a rich set of common operations including iteration, slicing, sorting, and concatenation.

Group sequence types by element types:

- Container Sequences (can hold items of different types):

listtuplecollections.deque

- Flat Sequences (hold items of one type):

strbytesbytearraymemoryviewarray.array

Container sequences hold references to the objects they contain, which may be of any type, while flat sequences physically store the value of each item within its own memory space, and not as distinct objects. Thus, flat sequences are more compact, but they are limited to holding primitive values like characters, bytes, and numbers.

Group sequence types by mutability:

- Mutable Sequences

listbytearrayarray.arraycollections.dequememoryview

- Immutable Sequences

tuplestrbytes

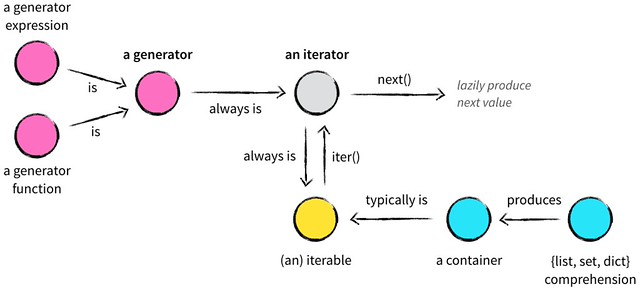

2.2 listcomps / genexps

my_list = [x**2 for x in range(0, 10)] # list comprehension

my_tuple = tuple(x**2 for x in range(0, 10)) # generator expression

import array

# Both OK; "I" for unsigned int. See https://docs.python.org/3/library/array.html

my_array_1 = array.array("I", (i**2 for i in range(0, 10))) # generator expression

my_array_2 = array.array("I", [i**2 for i in range(0, 10)]) # list comprehension

N.B. my_tuple above is NOT a good example of generator because actually (x**2 for x in range(0, 10)) is indeed a generator expression and returns a generator. The code of my_tuple above is NOT equal to:

my_gen = (x**2 for x in range(0, 10)) # OK. my_gen is a generator object

my_tuple = tuple(my_gen) # OK, but my_tuple == ()

my_tuple = tuple(*my_gen) # Syntax Error

so tuple(x**2 for x in range(0, 10)) is actually a special constructor of tuple. You cannot construct a tuple from a generator object manually.

To better understand generators, please read:

- nvie: Iterables vs. Iterators vs. Generators

- PEP 255 - Simple Generators

- stack overflow: Understanding Generators in Python

2.3 Tuples Are Not Just Immutable Lists

2.3.1 Tuples as Records

point_a = (-1, 1)

point_b = (2, 3)

2.3.2 Tuple Unpacking

point_a = (-1, 1)

x_a, y_a = point_a

print(x_a) # -1

print(y_a) # 1

An elegant application of tuple unpacking is swapping the values of variables without using a temporary variable:

b, a = a, b

2.3.3 Nested Tuple Unpacking

top_left, top_right, bottom_left, bottom_right = (0, 1), (1, 1), (0, 0), (1, 0)

square = (top_left, top_right, bottom_left, bottom_right)

(top_left_x, top_left_y), (top_right_x, top_right_y) = square[0:2]

Note that: square[0:2] == ((0, 1), (1, 1)) while square[0] == (0, 1) not ((0, 1)). In fact, python will evaluate ((0, 1)) as (0, 1).

2.3.4 namedtuple

The collections.namedtuple(typename, field_names) is a factory function that produces subclasses of tuple named typename and enhanced with accessibility via field_names. 一般的用法是:

import collections

Point = namedtuple('Point', ['x', 'y'])

p_a = Point(0, 1)

print(p_a.x) # 0

print(p_a[1]) # 1

为啥要 typename = namedtuple(typename, ...)?这是因为这个 “subclasses of tuple named typename” 是在它 constructor 内部的一个临时 namespace 创建的 (通过 exec),然后这个 subclass typename 的实体会被 constructor 返回,但是它的 name — 也就也是 typename — 并不会随着 return 被带到 constructor 所在的 namespace。我们在外部再赋值一下,主要是为了保持一致,使得这个 subclass 的 name 不管是在它创建的临时 namespace 里还是当前的 namespace 里都叫 typename,避免产生不必要的误解。当然,你写成 Bar = namedtuple('Foo', ...) 是合法的,是没有问题的。

更多内容可以参见:

- How namedtuple works in Python 2.7

- Breakdown: collections.namedtuple

- Be careful with exec and eval in Python

- Python collections source code

2.4 Slicing

在 2.1 我们讲过,所有的 sequence type 都支持 “iteration, slicing, sorting, and concatenation”.

To evaluate the expression seq[start:stop:step], Python calls seq[slice(start, stop, step)] then seq.__getitem__(slice(start, stop, step)). (因为 1. 里有讲 __getitem__ method delegates to [] operator)

start 默认是 0;stop 默认是 len(seq) (exclusively);step 默认是 1,而且它是连冒号也可以省略的。E.g.

s = 'bicycle's[:2] == s[0:2] == s[:2:] == s[0:2:] == s[:2:1] == s[0:2:1] == 'bi's[2:] == ... == 'cycle's[::2] == bcce

Instead of filling your code with hardcoded slices, you can name them. 比如一个固定格式的 invoice 字符串,它的 price、description 什么的都是定长的,我们可以这样:

price = slice(start1, stop1, [step1])

desc = slice(start2, stop2, [step2])

for invoice in invoice_list:

print(invoice[price], invoice[desc])

对于取下来的 sequence slice,我们可以直接用赋值来修改这个 sequence slice 进而直接修改 sequence 的值。这进一步说明:sequence slice 其实是 reference. E.g.

>>> l = list(range(10))

>>> l

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

>>> l[2:5] = [20, 30]

>>> l

[0, 1, 20, 30, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

>>> del l[5:7]

>>> l

[0, 1, 20, 30, 5, 8, 9]

>>> l[3::2] = [11, 22]

>>> l

[0, 1, 20, 11, 5, 22, 9]

>>> l[2:5] = 100

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: can only assign an iterable

>>> l[2:5] = [100]

>>> l

[0, 1, 100, 22, 9]

When the target of the assignment is a slice, the right side must be an iterable object, even if it has just one item.

The [] operator can also take multiple indexes or slices separated by commas. This is used, for instance, in the external NumPy package, where items of a two-dimensional numpy.ndarray can be fetched using the syntax a[i, j] and a two-dimensional slice obtained with an expression like a[m:n, k:l]. 实现上,它们的 __getitem__() 和 __setitem__() 是接收 tuple 的,比如:to evaluate a[i, j], Python calls a.__getitem__((i, j)).

The Ellipsis object — written as three full stops ... — is the single instance of the ellipsis class. NumPy uses ... as a shortcut when slicing arrays of many dimensions; for example, if x is a fourdimensional array, x[i, ...] is a shortcut for x[i, :, :, :,].

2.5 Using + and * with Sequences

Beware of expressions like a * n when a is a sequence containing mutable items. E.g. my_list = [[]] * 3 will result in a list with three references to the same inner list.

创建一个预分配长度为 5 的 list 我们可以用 lst = [None] * 5。那么现在我要一个 [lst, lst, lst] 的 list of lists 该怎么办?

llst = [[None] * 5 for _ in range(3)] # OK

lref = [[None] * 5] * 3 # Legal but this is a list of 3 references to one list of 5

鉴定是 list of lists 还是 list of references 可以用 id() 方法,类似 java 的 hashcode。

In [3]: for lst in llst:

...: print(id(lst))

...:

2343147973832

2343148089224

2343148087880

In [5]: for lst in lref:

...: print(id(lst))

...:

2343148276680

2343148276680

2343148276680

2.6 lst.sort() vs sorted(lst)

lst.sort()sorts in place—that is, without making a copy oflst.- A drawback: cannot cascade calls to other methods.

sorted(lst)creates a new list and returns it.lstdoes not change.

这两个方法的参数都是一样的:

reverse: booleankey: the function that will be applied to items to generate the sorting key.- 默认是 identity function,相当于是

key = lambda x:x,直接比较 item 本身 - 比如

key = str.lowermeans sorting case-insensitively - 比如

key = lenmeans sorting by the length of each item - 比如

key = intmeans sorting by values ofint(item)

- 默认是 identity function,相当于是

2.7 Managing Ordered Sequences with bisect Module

bisection 中文意思就是 “二分法”。

bisect.bisect(haystack, needle) does a binary search for needle in haystack — which must be a sorted sequence — and returns the index where needle can be inserted while maintaining haystack in ascending order.

You could use the result of bisect.bisect(haystack, needle) as the index argument to haystack.insert(index, needle) — however, using bisect.insort(haystack, needle) does both steps, and is faster.

See Python: Binary Search / Bisection / Binary Search Tree (BST).

2.8 When a List Is Not the Answer

2.8.1 array.array

If the list will only contain numbers, an array.array is more efficient than a list.

When creating an array.array, you provide a typecode, a letter to determine the underlying C type used to store each item in the array.

- For example,

'b'is the typecode for signed char. If you create anarray('b'), then each item will be stored in a single byte and interpreted as an integer from $–128$ to $127$. - For large sequences of numbers, this saves a lot of memory.

- E.g. an

array('f')does not holdfloatobjects but only the bytes representing the values.

- E.g. an

- And Python will not let you put any number that does not match the type for the array.

2.8.2 memoryview(array)

一个 array 可以有多种表示,比如二进制、八进制。memoryview 就是用来显示这些不同的表示的。如果修改 memoryview 自然会修改到底层的 array 的值。这进一步说明:sequence 是 mutable 的。

>>> numbers = array.array('h', [-2, -1, 0, 1, 2]) # 'h' for signed short

>>> memv = memoryview(numbers)

>>> memv_oct = memv.cast('B') # 'B' for unsigned char

>>> memv_oct.tolist()

[254, 255, 255, 255, 0, 0, 1, 0, 2, 0]

2.8.3 collections.deque and Other Queues

collections.deque is a thread-safe double-ended queue designed for fast inserting and removing from both ends.

Chapter 3 - Dictionaries and Sets

Digress: What Is Hashable?

An object is hashable if it has a hash value which never changes during its lifetime (it needs a __hash__() method), and can be compared to other objects (it needs an __eq__() method). Hashable objects which compare equal must have the same hash value.

- The atomic immutable types (str, bytes, numeric types) are all hashable.

- A

frozensetis always hashable, because its elements must be hashable by definition. - A

tupleis hashable only if all its items are hashable.- At the time of this writing, the Python Glossary states: “All of Python’s immutable built-in objects are hashable” but that is inaccurate because a tuple is immutable, yet it may contain references to unhashable objects.

>>> tt = (1, 2, (30, 40))

>>> hash(tt)

8027212646858338501

>>> tl = (1, 2, [30, 40])

>>> hash(tl)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

>>> tf = (1, 2, frozenset([30, 40]))

>>> hash(tf)

-4118419923444501110

User-defined types are hashable by default because their hash value is their id() and they all compare not equal.

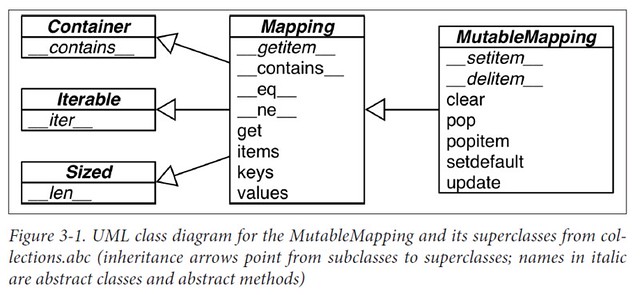

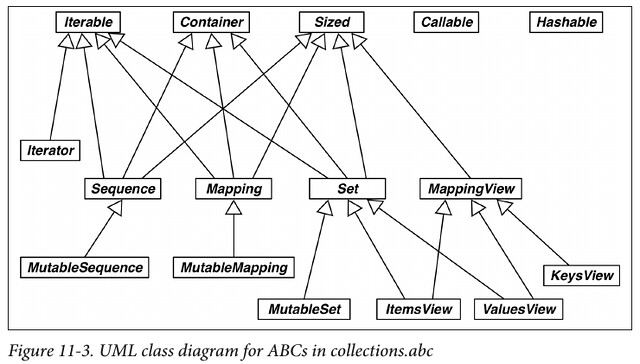

3.1 Generic Mapping Types

In [6]: from collections import abc

In [7]: isinstance({}, abc.MutableMapping)

Out[7]: True

All mapping types in the standard library use the basic dict in their implementation, so they share the limitation that the keys must be hashable.

3.2 dictcomp

创建 dict 的语法真是多种多样……

>>> a = dict(one=1, two=2, three=3)

>>> b = {'one': 1, 'two': 2, 'three': 3}

>>> c = dict(zip(['one', 'two', 'three'], [1, 2, 3]))

>>> d = dict([('two', 2), ('one', 1), ('three', 3)])

>>> e = dict({'three': 3, 'one': 1, 'two': 2})

>>> a == b == c == d == e

True

In addition to the literal syntax and the flexible dict constructor, we can use dict comprehensions to build dictionaries.

>>> DIAL_CODES = [

... (86, 'China'),

... (91, 'India'),

... (1, 'United States'),

... (62, 'Indonesia'),

... (55, 'Brazil'),

... (92, 'Pakistan'),

... (880, 'Bangladesh'),

... (234, 'Nigeria'),

... (7, 'Russia'),

... (81, 'Japan'),

... ]

>>> country_code = {country: code for code, country in DIAL_CODES}

>>> country_code

{'China': 86, 'India': 91, 'Bangladesh': 880, 'United States': 1,

'Pakistan': 92, 'Japan': 81, 'Russia': 7, 'Brazil': 55, 'Nigeria':

234, 'Indonesia': 62}

>>> {code: country.upper() for country, code in country_code.items() if code < 66}

{1: 'UNITED STATES', 55: 'BRAZIL', 62: 'INDONESIA', 7: 'RUSSIA'}

3.3 Handling Missing Keys with dict.setdefault()

d.get(k, default) is an alternative to d[k] whenever a default value is more convenient than handling KeyError.

setdefault(key[, default]):

- If

keyis ind, returnd[key]. - If not, insert

d[key] = defaultand returndefault. defaultdefaults toNone.

与 [] 可以组合成这么一个 combo:

d.setdefault(key, []).append(new_value)

- 如果

d[key]存在,就 append - 如果

d[key]不存在,就创建一个[]然后 append

3.4 Handling Missing Keys with collections.defaultdict or __missing__()

defaultdict(default_factory):

default_factoryis a callable that is used to produce a default value whenever__getitem__(key)is called with a nonexistentkey.- N.B only for

__getitem__()calls. Therefore ifddis adefaultdictandkeyis a missing key:dd[key]will return the default value created bydefault_factory()dd.get(k)will returnNone

Another way to handle missing keys is to extend a dict and implement the __missing__() method.

__missing__()is just called by__getitem__()

3.5 Variations of dict

collections.OrderedDict: Maintains keys in insertion order.collections.ChainMap(dict1, dict2):- 先在

dict1里查,有就 return;没有就继续去dict2里查。 dict1和dict2可以有相同的 key。- 查找的顺序只和构造器的参数顺序有关。

- 先在

collections.Counter: A mapping that holds an integer count for each key. Updating an existing key adds to its count.

3.6 Subclassing UserDict

UserDict is designed to be subclassed. It’s almost always easier to create a new mapping type by extending UserDict rather than dict.

Note that UserDict does not inherit from dict, but has an internal dict instance, called data, which holds the actual items.

- 组合优于继承 again!

- 所以

UserDict既不是一个 interface 也不是一个 abstract class,它是一个 Mixin

3.7 Immutable Mappings

The mapping types provided by the standard library are all mutable, but you may need to guarantee that a user cannot change a mapping by mistake.

Since Python 3.3, the types module provides a wrapper class called MappingProxyType, which, given a mapping, returns a mappingproxy instance that is a read-only but dynamic view of the original mapping. This means that updates to the original mapping can be seen in the instance, but changes cannot be made through it.

>>> from types import MappingProxyType

>>> d = {1: 'A'}

>>> d_proxy = MappingProxyType(d)

>>> d_proxy

mappingproxy({1: 'A'})

>>> d_proxy[1]

'A'

>>> d_proxy[2] = 'x'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'mappingproxy' object does not support item assignment

>>> d[2] = 'B'

>>> d_proxy

mappingproxy({1: 'A', 2: 'B'})

>>> d_proxy[2]

'B'

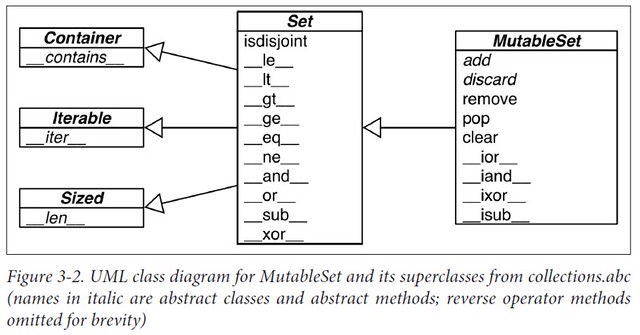

3.8 set

setelements must be hashable.setitself is not hashable.frozensetis hashable, so you can havefrozensetinside aset

3.8.1 set Literals

s = {1, 2, 3}

- To create an empty set, you should use the constructor without an argument:

s = set(). - If you write

s = {}, you’re creating an emptydict.

3.8.2 setcomp

>>> from unicodedata import name

>>> {chr(i) for i in range(32, 256) if 'SIGN' in name(chr(i), '')}

{'§', '=', '¢', '#', '¤', '<', '¥', 'μ', '×', '$', '¶', '£', '©',

'°', '+', '÷', '±', '>', '¬', '®', '%'}

3.8.3 Set Operations

Given two sets a and b and an element e:

a & b: the intersection;a | b: the union;a - b: the difference!a < b: isaa proper subset ofb?a <= b: isaa subset ofb?a > b: isaa proper superset ofb?a >= b: isaa superset ofb?a.discard(e): removeefromaif it is presenta.remove(e): removeefroma, raisingKeyErrorifenot ina

3.9 dict and set Under the Hood

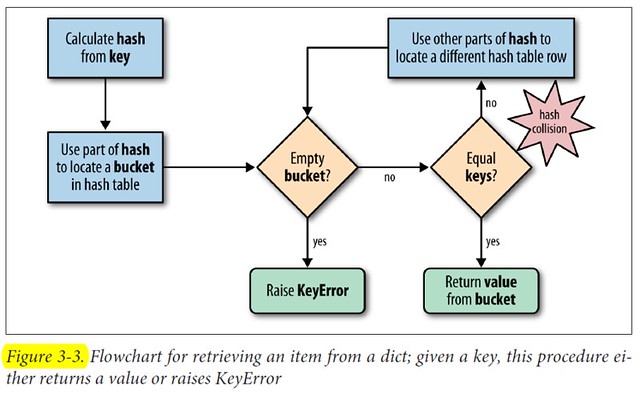

A hash table is a sparse array (i.e., an array that always has empty cells). In standard data structure texts, the cells in a hash table are often called “buckets.” In a dict hash table, there is a bucket for each item, and it contains two fields: a reference to the key and a reference to the value of the item. Because all buckets have the same size, access to an individual bucket is done by offset.

The hash() built-in function works directly with built-in types and falls back to calling __hash__() for user-defined types. If two objects compare equal, their hash values must also be equal. For example, because 1 == 1.0 is true, hash(1) == hash(1.0) must also be true, even though the internal representation of an int and a float are very different.

To fetch the value at my_dict[search_key], Python calls hash(search_key) to obtain the hash value of search_key and uses the least significant bits of that number as an offset to look up a bucket in the hash table (the number of bits used depends on the current size of the table). If the found bucket is empty, KeyError is raised. Otherwise, the found bucket has an item—a found_key:found_value pair—and then Python checks whether search_key == found_key. If they match, that was the item sought: found_value is returned.

However, if search_key and found_key do not match, this is a hash collision. In order to resolve the collision, the algorithm then takes different bits in the hash, massages them in a particular way, and uses the result as an offset to look up a different bucket. If that is empty, KeyError is raised; if not, either the keys match and the item value is returned, or the collision resolution process is repeated.

The process to insert or update an item is the same, except that when an empty bucket is located, the new item is put there, and when a bucket with a matching key is found, the value in that bucket is overwritten with the new value.

Additionally, when inserting items, Python may determine that the hash table is too crowded and rebuild it to a new location with more room. As the hash table grows, so does the number of hash bits used as bucket offsets, and this keeps the rate of collisions low.

dicts have significant memory overhead

Because a dict uses a hash table internally, and hash tables must be sparse to work, they are not space efficient. For example, if you are handling a large quantity of records, it makes sense to store them in a list of tuples or named tuples instead.

But remember:

Optimization is the altar where maintainability is sacrificed.

Key search is very fast

The dict implementation is an example of trading space for time: dictionaries have significant memory overhead, but they provide fast access regardless of the size of the dictionary — as long as it fits in memory.

Adding items to a dict may change the order of existing keys

Whenever you add a new item to a dict, the Python interpreter may decide that the hash table of that dictionary needs to grow. This entails building a new, bigger hash table, and adding all current items to the new table. During this process, new (but different) hash collisions may happen, with the result that the keys are likely to be ordered differently in the new hash table. All of this is implementation-dependent, so you cannot reliably predict when it will happen. If you are iterating over the dictionary keys and changing them at the same time, your loop may not scan all the items as expected.

This is why modifying the contents of a dict while iterating through it is a bad idea. If you need to scan and add items to a dictionary, do it in two steps: read the dict from start to finish and collect the needed additions in a second dict. Then update the first one with it.

How Sets Work

The set and frozenset types are also implemented with a hash table, except that each bucket holds only a reference to the element.

The underlying hash table determines the behavior of a dict applies to a set. Without repeating the previous section, we can summarize it for sets with just a few words:

setelements must be hashable objects.sets have a significant memory overhead.- Membership testing is very efficient.

- Adding elements to a

setmay change the order of other elements.

Chapter 4 - Text vs Bytes

4.1 Character Issues

The Unicode standard explicitly separates the identity of characters from specific byte representations. 我们来学习一下相关的词汇:

- code point: the identity of a character. 也就是我们所谓的 “Unicode 编码”,比如 “A” 的 code point 就是 “U+0041”

- code points $\rightarrow$ bytes 的过程我们称为 encoding;

- bytes $\rightarrow$ code points 的过程我们称为 decoding;

- encode 可以理解为 “编成机器码”,byte 也是一种码嘛~

- 但同时 encoding 这个词也可以表示这一套编解码的规则:An encoding is an algorithm that converts code points to byte sequences and vice versa.

- codec 是 coder-decoder 的简称,co(der)-dec(oder)

- 我们也可以理解为一套 encoding 规则对应一个 codec

- code page 则是一张 $\operatorname{f}: \text{code point} \rightarrow \text{byte}$ 的 lookup table

>>> s = 'café'

>>> b = s.encode('utf8') # Encode `str` to `bytes` using UTF-8 encoding.

>>> b

b'caf\xc3\xa9' # `bytes` literals start with a `b` prefix.

>>> b.decode('utf8') # Decode `bytes` to `str` using UTF-8 encoding.

'café'

Digress: BOM

BOM stands for Byte-Order Mark.

The UTF-8 BOM is a sequence of bytes that allows the reader to identify a file as being encoded in UTF-8.

Normally, the BOM is used to signal the endianness of an encoding, but since endianness is irrelevant to UTF-8, the BOM is unnecessary.

| BOM Bytes | Encoding Form |

|---|---|

| “00 00 FE FF” | UTF-32, big-endian |

| “FF FE 00 00” | UTF-32, little-endian |

| “FE FF” | UTF-16, big-endian |

| “FF FE” | UTF-16, little-endian |

| “EF BB BF” | UTF-8 |

4.2 Byte Essentials

The new binary sequence types are unlike the Python 2 str in many regards. The first thing to know is that there are two basic built-in types for binary sequences: the immutable bytes type introduced in Python 3 and the mutable bytearray, added in Python 2.6. (Python 2.6 also introduced bytes, but it’s just an alias to the str type, and does not behave like the Python 3 bytes type.)

Each item in bytes or bytearray is an integer from 0 to 255, and not a one-character string like in the Python 2 str.

my_bytes[0]retrieves an intmy_bytes[:1]returns a bytes object of length 1 (i.e. always a sequence)- however,

my_str[0] == my_str[:1]

4.3 Basic Encoders/Decoders

Each codec has a name, like utf_8, and often aliases, such as utf8, utf-8, and U8. 其他常见的 codec 还有:

latin1a.k.a.iso8859_1cp1252cp437gb2312utf-16le

4.4 Understanding Encode/Decode Problems (略)

4.5 Handling Text Files

If the encoding argument was omitted when opening the file to write, the locale default encoding would be used. Always pass an explicit encoding= argument when opening text files.

- On GNU/Linux and OSX all of these encodings are set to UTF-8 by default, and have been for several years.

- On Windows, not only are different encodings used in the same system, but they are usually codepages like

cp850orcp1252that support only ASCII with 127 additional characters that are not the same from one encoding to the other.

4.6 Normalizing Unicode for Saner Comparisons (略)

4.7 Sorting Unicode Text (略)

4.8 The Unicode Database (略)

4.9 Dual-Mode str and bytes APIs (略)

Part III - Functions as Objects

Chapter 5 - Python Functions are First-Class Objects

Programming language theorists define a “first-class object” as a program entity that can be:

- Created at runtime

- Assigned to a variable or element in a data structure

- Passed as an argument to a function

- Returned as the result of a function

Integers, strings, and dictionaries are other examples of first-class objects in Python.

5.1 Treating a Function Like an Object

>>> def factorial(n):

... '''returns n!'''

... return 1 if n < 2 else n * factorial(n-1)

...

>>> factorial.__doc__

'returns n!'

>>> type(factorial)

<class 'function'>

>>> help(factorial)

Help on function factorial in module __main__:

factorial(n)

returns n!

>>> fact = factorial

>>> list(map(fact, range(11)))

[1, 1, 2, 6, 24, 120, 720, 5040, 40320, 362880, 3628800]

map(func, iterable)returns an generator (anmapobject) where each item is the result offunc(e)whereeis an element ofiterable- Actually less than a listcomp here:

list(map(fact, range(11))) == [fact(x) for x in range(11)]list(map(None, iter_a, iter_b)) == [(a,b) for a in iter_a for b in iter_b]

简单说 map 就是:

def map(func, iterable):

for i in iterable:

yield func(i)

5.2 Higher-Order Functions (e.g. map, filter and reduce)

A function that takes a function as argument or returns a function as the result is a higher-order function. E.g. map, filter and reduce.

apply was deprecated in Python 2.3 and removed in Python 3. apply(fn, args, kwargs) == fn(*args, **kwargs)

简单说 filter 就是:

def filter(func, iterable):

for i in iterable:

if func(i):

yield i

E.g.

list(filter(lambda x: x % 2, range(11)))

== [x for x in range(11) if x % 2]

== [1,3,5,7,9]

而 reduce(func, iterable) 的作用是:apply two-argument function func cumulatively to the items of iterable, so as to reduce the iterable to a single value.

def reduce(function, iterable, initializer=None):

it = iter(iterable)

if initializer is None:

try:

initializer = next(it)

except StopIteration:

raise TypeError('reduce() of empty sequence with no initial value')

accum_value = initializer

for x in it:

accum_value = function(accum_value, x)

return accum_value

E.g.

from functools import reduce

from operator import add

reduce(add, [1,2,3,4,5])

== (((1+2)+3)+4)+5

== 15

If seq=[s1, s2, s3, ... , sn], calling reduce(func, seq) works like this:

- At first the first two elements of

seqwill be applied tofunc, i.e.func(s1, s2). The list on whichreduce()works looks now like this:[func(s1, s2), s3, ..., sn] - In the next step

funcwill be applied on the previous result and the third element of the list, i.e.func(func(s1, s2), s3). The list looks like this now:[func(func(s1, s2),s3), s4, ..., sn] - Continue like this until just one element is left and return this element as the result of

reduce()

P.S. Other reducing built-ins are all and any:

all(iterable)- Returns

Trueif every element of theiterableis truthy; all([])returnsTrue.

- Returns

any(iterable)- Returns

Trueif any element of theiterableis truthy; any([])returnsFalse.

- Returns

5.3 Anonymous Functions

The lambda keyword creates an anonymous function within a Python expression.

The body of lambda functions must be pure expressions. In other words, the body of a lambda cannot make assignments or use any other Python statement such as while, try, etc.

5.4 The 7 Flavors of Callable Objects

() in func() can be called a “call opertor”. To determine whether an object is callable, use the callable() built-in function.

- User-defined functions. E.g. created with

deforlambda. - User-defined methods.

- Built-in functions. Functions implemented in C (for CPython), like

len. - Built-in methods. Methods implemented in C (for CPython), like

dict.get. - Class instructors. When invoked, a class runs its

__new__method to create an instance, then__init__to initialize it, and finally the instance is returned to the caller. Because there is nonewoperator in Python, calling a class is like calling a function. - Callable class instances. If a class implements a

__call__method, then its instances can be invoked as functions. - Generators. Functions or methods that use

yield.

5.5 User-Defined Callable Types

A class implementing __call__ is an easy way to create functions that have some internal state that must be kept across invocations. 注意这句其实说的就是:在某些需要 function 的场合,我们可以用 callable class instance 来代替 function,从而可以给这个 “function” 一些 state 来实现更多的功能。原文说的是 “…to create function-like objects that…“,不知道为何要这么拐弯抹角的表示……E.g. decorators must be functions, 但比如你要做一个 cache decorator,这时就需要将这个 decorator 用 callable class instance 来实现,把 cache 封装到 class 内部。

A totally different approach to creating functions with internal state is to use closures. Closures, as well as decorators, are the subject of Chapter 7.

5.6 Function Introspection

General way to introspect an object:

dir(obj): returns a list of valid attributes for that objectobj.__dict__: stores all the user attributes assigned to that object

Exclusive way to introspect a user-defined function:

func.__annotations__: a dict; the parameter and return annotations- 注意 annotation 不同于 docstring (

'''blah blah''') which is stored infunc.__doc__

- 注意 annotation 不同于 docstring (

func.__closure__: a tuple of closure cells; the function closure, i.e. bindings for free variables (one cell for each free variable)func.__code__: acodeobject; function metadata and function body compiled into bytecodefunc.__defaults__: a tuple of default values for the formal parametersfunc.__kwdefaults__: a dict of default values for the keyword-only formal parameters

Function Annotations

注意 python 的 annotation 不同于的 java 的 annotation;python 的 annotation 是为 documentation 服务的,最详细的说明在 PEP 3107 – Function Annotations。annotation 可以有两种形式:一是 string,二是 type,我们来看下规范:

def foo(a: "annotation for a" [= a_def_val]) -> "annotaton for returned value":

pass

def bar(a: TypeA (= a_def_val)) -> ReturnType:

pass

举个例子:

def foo(a: "this is parameter a") -> "return nothing":

return None

>>> foo.__annotations__

>>> {'a': 'this is parameter a', 'return': 'return nothing'}

class ReturnType: pass

def bar(a: int = 1) -> ReturnType:

pass

>>> bar.__annotations__

>>> {'a': int, 'return': __main__.ReturnType}

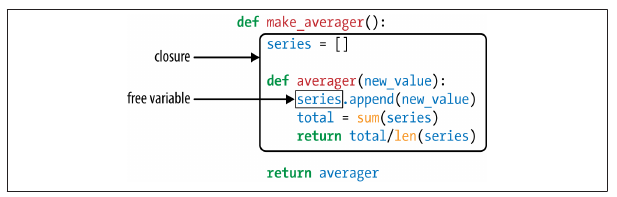

Function Closure

先看例子:

def print_msg(msg):

'''This is the outer enclosing function'''

def printer():

'''This is the nested function'''

print(msg)

return printer

print_hello = print_msg("Hello")

print_hello() # Output: Hello

>>> print_hello.__closure__

>>> (<cell at 0x000001B2408F6C78: str object at 0x000001B240A34110>,)

>>> inspect.getclosurevars(print_hello)

>>> ClosureVars(nonlocals={'msg': 'Hello'}, globals={}, builtins={'print': <built-in function print>}, unbound=set())

这里的 msg = 'Hello' 是 print_hello 的一个 free variable。我们先来看下 free variable 的定义:

- In mathematics:

- a free variable is a variable in an expression where substitution may take place.

- 也就是说,能做替换操作的 variable 都是 free variable

- a bound variable is a variable that was previously free, but has been bound to a specific value or set of values.

- E.g., the variable $x$ becomes a bound variable when we write:

- $\forall x, (x + 1)^2 = x^2 + 2x + 1$, or

- $\exists x \text{ such that } x^2 = 2$

- Some older books use the terms real variable and apparent variable for free variable and bound variable.

- E.g., the variable $x$ becomes a bound variable when we write:

- a free variable is a variable in an expression where substitution may take place.

- In computer programming:

- the term free variable refers to variables used in a function that are neither local variables nor parameters of that function.

- 这个场合下,bound variable 就不好定义了,也没有必要往这个方向去考虑。

所以在 python 这儿,如果 func.__closure__ 就是 closure 的话,那 closure 相当于被定义成了 free variable 的一个 enviroment 或者 namespace. 我觉得这么理解其实挺好记的,非常直观 (毕竟你可以直接 print 到 console……)。

我对 closure 一直不理解是因为我看到了各种各样的定义,比如:

- “function + its free variables”, or the code snippet of “function + its free variables”

- The function object itself (i.e.

print_hellohere) - A phenomenon which happens when a function has access to a local variable from an enclosing scope.

这些统统没有 func.__closure__ 直观,所以暂且按 func.__closure__ 来记好了。若是以后对 closure 的理解出了偏差,还可以甩锅给 python 说它变量名起得不对 www

参考 Variable / Bound Variable / Free Variable / Scope / Closure.

Default Parameter Values vs Default Keyword-Only Parameter Values

按 PEP 3102 – Keyword-Only Arguments 的说法,kwyword-only argument 是:

Arguments that can only be supplied by keyword and which will never be automatically filled in by a positional argument.

def func(a, b = 1, *args, kwa, kwb = 2):

pass

>>> func.__defaults__

>>> (1,)

>>> func.__kwdefaults__

>>> {'kwb': 2}

从逻辑上,keyword-only parameter 是 parameter 的一种 (其实一共就两种,一个 positional 一个 keyword-only),但是上面这个例子里 __kwdefaults__.values $\not \subset$ __defaults__.

另外一个需要注意的问题是:default parameter value 只在 def 的被执行的时候初始化一次,而不是每次调用 function 的时候都初始化一次 (有点类似 static;Ruby 也是这样的)。比如下面这个例子:

def func2(b = [], *args, kwb = []):

b.append('F')

kwb.append('F')

print("b == {}".format(b))

print("kwb == {}".format(kwb))

for _ in range(3):

func2()

// output:

/**

b == ['F']

kwb == ['F']

b == ['F', 'F']

kwb == ['F', 'F']

b == ['F', 'F', 'F']

kwb == ['F', 'F', 'F']

**/

所以如果你要每次调用 function 时都默认参数为 [],正确的写法应该是:

def func3(b = None):

if b is None

b = []

......

当然这个特性也可以合理利用,比如你要做一个 cache,你当然不希望每次都初始化为默认的值。

注意这章一开始有说 Python functions are first-class objects,所以 default parameter value 也有点像 object 的 attribute.

5.7 Packages for Functional Programming: operator and functools

5.7.1 operator: arithmetic operators / itemgetter / attrgetter / methodcaller

Python does not aim to be a functional programming language, but a functional coding style can be used to good extent, thanks to the support of packages like operator and functools.

To save you the trouble of writing trivial anonymous functions like lambda a, b: a*b, the operator module provides function equivalents for dozens of arithmetic operators.

from functools import reduce

from operator import mul

def fact(n): # lambda version

return reduce(lambda a, b: a*b, range(1, n+1))

def fact(n): # operator version

return reduce(mul, range(1, n+1))

Another group of one-trick lambdas that operator replaces are functions to pick items from sequences or read attributes from objects: itemgetter and attrgetter actually build custom functions to do that.

- Essentially,

itemgetter(1)does the same aslambda fields: fields[1] - If you pass multiple index arguments to

itemgetter(), the function it builds will return tuples with the extracted values itemgetter()uses the[]operator–it supports not only sequences but also mappings and any class that implements__getitem__().

metro_data = [

('Tokyo', 'JP', 36.933, (35.689722, 139.691667)),

('Delhi NCR', 'IN', 21.935, (28.613889, 77.208889)),

('Mexico City', 'MX', 20.142, (19.433333, -99.133333)),

('New York-Newark', 'US', 20.104, (40.808611, -74.020386)),

('Sao Paulo', 'BR', 19.649, (-23.547778, -46.635833)),

]

from operator import itemgetter

for city in sorted(metro_data, key=itemgetter(1)):

print(city)

# Output:

"""

('Sao Paulo', 'BR', 19.649, (-23.547778, -46.635833))

('Delhi NCR', 'IN', 21.935, (28.613889, 77.208889))

('Tokyo', 'JP', 36.933, (35.689722, 139.691667))

('Mexico City', 'MX', 20.142, (19.433333, -99.133333))

('New York-Newark', 'US', 20.104, (40.808611, -74.020386))

"""

cc_name = itemgetter(1, 0)

for city in metro_data:

"""

注意 itemgetter(...) 等价于一个 lambda

所以它本身是一个 function

既然是 function 自然就可以 call

(换言之 itemgetter 是一个 "return function 的 function")

"""

print(cc_name(city))

# Output:

"""

('JP', 'Tokyo')

('IN', 'Delhi NCR')

('MX', 'Mexico City')

('US', 'New York-Newark')

('BR', 'Sao Paulo')

"""

A sibling of itemgetter is attrgetter, which creates functions to extract object attributes by name.

- E.g.

attrgetter("__class__")("hello")return"hello".__class__(==<class 'str'>) - If you pass attrgetter several attribute names as arguments, it also returns a tuple of values.

- In addition, if any argument name contains a

.(dot), attrget ter navigates through nested objects to retrieve the attribute- E.g.

attrgetter('__class__.__name__')("hello")return"hello".__class__.__name__(=='str')

- E.g.

At last we cover methodcaller–the function it creates calls a method by name on the object given as argument:

from operator import methodcaller

s = 'The time has come'

upcase = methodcaller('upper')

upcase(s)

# 'THE TIME HAS COME'

hiphenate = methodcaller('replace', ' ', '-')

hiphenate(s)

# 'The-time-has-come'

总结一下:

def itemgetter(*keys):

if len(keys) == 1:

key = keys[0]

return lambda x: x[key]

else:

return lambda x: tuple(x[key] for key in keys)

def attrgetter(*names):

if any(not isinstance(name, str) for name in names):

raise TypeError('attribute name must be a string')

if len(names) == 1:

name = names[0]

return lambda x: x.__getattribute__(name)

else:

return lambda x: tuple(x.__getattribute__(name) for name in names)

def methodcaller(name, *args, **kwargs):

return lambda x: getattr(x, name)(*args, **kwargs)

get_first_two_items = itemgetter(0, 1)

# is equivalent to define

def get_first_two_items(x):

return (x[0], x[1])

get_foo_and_bar = attrgetter("foo", "bar")

# is equivalent to define

def get_foo_and_bar(x):

return (x.foo, x.bar)

call_foo_with_bar_and_baz = methodcaller("foo", "bar", baz="baz")

call_foo_with_bar_and_baz(f)

# is equivalent to call

f.foo("bar", baz="baz")

5.7.2 functools: Freezing Arguments with partial()

from operator import mul

from functools import partial

triple = partial(mul, 3)

triple(7)

# Output: 21

Chapter 6 - Design Patterns with First-Class Functions

6.1 Case Study: Refactoring Strategy

第一个例子,注意两点:

- package

abc名字的意思是 abstract base class…… - 写 empty function body 的两种方式:

pass- 连

pass都不用写,只留下 docstring

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Order:

def __init__(self, customer, cart, promotion=None):

self.customer = customer

self.cart = list(cart)

self.promotion = promotion

def due(self):

if self.promotion is None:

discount = 0

else:

discount = self.promotion.discount(self)

return self.total() - discount

# In Python 3.4, the simplest way to declare an ABC is to subclass `abc.ABC`

class Promotion(ABC): # the Strategy: an abstract base class

@abstractmethod

def discount(self, order):

"""Return discount as a positive dollar amount"""

# pass

class FidelityPromo(Promotion): # first Concrete Strategy

"""5% discount for customers with 1000 or more fidelity points"""

def discount(self, order):

return order.total() * .05 if order.customer.fidelity >= 1000 else 0

class BulkItemPromo(Promotion): # second Concrete Strategy

"""10% discount for each LineItem with 20 or more units"""

def discount(self, order):

discount = 0

for item in order.cart:

if item.quantity >= 20:

discount += item.total() * .1

return discount

class LargeOrderPromo(Promotion): # third Concrete Strategy

"""7% discount for orders with 10 or more distinct items"""

def discount(self, order):

distinct_items = {item.product for item in order.cart}

if len(distinct_items) >= 10:

return order.total() * .07

return 0

Each concrete strategy above is a class with a single method, discount. Furthermore, the strategy instances have no state (no instance attributes). You could say they look a lot like plain functions, and you would be right. We can refactor this example to function-oriented:

class Order:

def __init__(self, customer, cart, promotion=None):

self.customer = customer

self.cart = list(cart)

self.promotion = promotion

def due(self):

if self.promotion is None:

discount = 0

else:

discount = self.promotion(self) # 精妙之处在此

return self.total() - discount

def fidelity_promo(order):

"""5% discount for customers with 1000 or more fidelity points"""

return order.total() * .05 if order.customer.fidelity >= 1000 else 0

def bulk_item_promo(order):

"""10% discount for each LineItem with 20 or more units"""

discount = 0

for item in order.cart:

if item.quantity >= 20:

discount += item.total() * .1

return discount

def large_order_promo(order):

"""7% discount for orders with 10 or more distinct items"""

distinct_items = {item.product for item in order.cart}

if len(distinct_items) >= 10:

return order.total() * .07

return 0

6.1.1 Flyweight Pattern

It is interesting to note that in Design Patterns the authors suggest: “Strategy objects often make good flyweights.” A definition of the Flyweight in another part of that work states:

A flyweight is a shared object that can be used in multiple contexts simultaneously.

flyweight 本意是拳击比赛的 “轻量级”。

这个定义并没有很清楚,这篇 Flyweight 我觉得写得不错。给出的例子是 game programming 中的地图渲染的场景:

- 你有很多很多个

Treeobject 要渲染 - 但是你可以只存一个 static 或者 singleton 的

TreeModelobject,记录树的多边形、颜色等等信息 (假设你地图上所有的树都长一样) - 然后你的

Treeobject 就可以引用或者指向这个TreeModelobject,然后再保存 coordinate 这些自身 specific 的信息 - 这样比较省空间的

Treeobject 我们成为 flyweight object

总结得也不错:

Flyweight, like its name implies, comes into play when you have objects that need to be more lightweight, generally because you have too many of them. The Flyweight pattern is purely about efficiency.

极端一点说,所有带 static 的 object 都可以看做 flyweight object.

6.1.2 Choosing the Best Strategy: Simple Approach

炫技一波:

promos = [fidelity_promo, bulk_item_promo, large_order_promo]

def best_promo(order):

"""Select best discount available"""

return max(promo(order) for promo in promos)

6.1.3 Advanced Approach: Finding Strategies in a Module

"""

globals():

Return a dictionary representing the current global symbol table. This is always the

dictionary of the current module (inside a function or method, this is the module

where it is defined, not the module from which it is called).

"""

promos = [globals()[name] for name in globals() if name.endswith('_promo') and name != 'best_promo']

def best_promo(order):

"""Select best discount available"""

return max(promo(order) for promo in promos)

Another way of collecting the available promotions would be to create a module, promotions.py, and put all the strategy functions there, except for best_promo.

promos = [func for name, func in inspect.getmembers(promotions, inspect.isfunction)]

6.2 Command Pattern

class MacroCommand:

"""A command that executes a list of commands"""

def __init__(self, commands):

self.commands = list(commands)

def __call__(self):

for command in self.commands:

command() ## Need implementation of `__call__` inside each command object

Part IV - Object-Oriented Idioms

Chapter 7 - Function Decorators and Closures

7.1 Decorators 101

A decorator is a callable which can take the decorated function as argument. (另外还有 class decorator)

Assume we have a decorator named foo,

@foo

def baz():

print('running baz')

# ----- is roughly equivalent to -----

def foo(func):

print('running foo')

return func

def baz():

print('running baz')

baz = foo(baz)

注意上面的例子中:

baz定义结束时,@foo会立即执行 (相当于替换了baz的定义)- 换言之,当

baz所在的 module 被 load 进来的时候,@foo就会执行

- 换言之,当

- 调用

baz()时并不会执行@foo

7.2 When Python Executes Decorators

A key feature of decorators is that they run right after the decorated function is defined. That is usually at import time.

Decorated functions are invoked at runtime of course.

7.3 Decorator-Enhanced Strategy Pattern

promos = [] # promotions registry

def promotion(promo_func):

promos.append(promo_func) # register this promotion

return promo_func

@promotion

def fidelity(order):

"""5% discount for customers with 1000 or more fidelity points"""

...

@promotion

def bulk_item(order):

"""10% discount for each LineItem with 20 or more units"""

...

@promotion

def large_order(order):

"""7% discount for orders with 10 or more distinct items"""

...

def best_promo(order):

"""Select best discount available"""

return max(promo(order) for promo in promos)

Pros:

- The promotion strategy functions don’t have to use special names.

- The

@promotiondecorator highlights the purpose of the decorated function, and also makes it easy to temporarily disable a promotion - Promotional discount strategies may be defined in other modules, anywhere in the system, as long as the

@promotiondecorator is applied to them.

7.4 Variable Scope Rules

Code that uses inner functions almost always depends on closures to operate correctly. To understand closures, we need to take a step back a have a close look at how variable scopes work in Python.

>>> b = 6

>>> def f2(a):

... print(a)

... print(b)

... b = 9

...

>>> f2(3)

3

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 3, in f2

UnboundLocalError: local variable 'b' referenced before assignment

The fact is, when Python compiles the body of the function, it decides that b is a local variable because it is assigned within the function. The generated bytecode reflects this decision and will try to fetch b from the local environment.

Try the following code to see bytecode:

>>> from dis import dis

>>> dis(f2)

1 0 RESUME 0

2 2 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (NULL + print)

12 LOAD_FAST 0 (a)

14 CALL 1

22 POP_TOP

3 24 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (NULL + print)

34 LOAD_FAST_CHECK 1 (b)

36 CALL 1

44 POP_TOP

4 46 LOAD_CONST 1 (9)

48 STORE_FAST 1 (b)

50 RETURN_CONST 0 (None)

This is not a bug, but a design choice: Python does not require you to declare variables, but assumes that a variable assigned in the body of a function is local.

If we want the interpreter to treat b as a global variable in spite of the assignment within the function, we use the global declaration:

>>> b = 6

>>> def f2(a):

... global b

... print(a)

... print(b)

... b = 9

...

>>> f2(3)

3

6

>>> b

9

>>> dis(f2)

1 0 RESUME 0

3 2 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (NULL + print)

12 LOAD_FAST 0 (a)

14 CALL 1

22 POP_TOP

4 24 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (NULL + print)

34 LOAD_GLOBAL 2 (b)

44 CALL 1

52 POP_TOP

5 54 LOAD_CONST 1 (9)

56 STORE_GLOBAL 1 (b)

58 RETURN_CONST 0 (None)

7.5 Closures

A closure is a function with an extended scope that encompasses nonglobal variables referenced in the body of the function but not defined there. It does not matter whether the function is anonymous or not; what matters is that it can access nonglobal variables that are defined outside of its body.

Consider the following example:

>>> avg = make_averager()

>>> avg(10)

10.0

>>> avg(11)

10.5

>>> avg(12)

11.0

Within averager, series is a free variable. This is a technical term meaning a variable that is not bound in the local scope. 我们也称 The closure for averager extends the scope of that function to include the binding for the free variable series.

Inspecting the free variable:

>>> avg.__code__.co_varnames

('new_value', 'total')

>>> avg.__code__.co_freevars

('series',)

The binding for series is kept in the __closure__ attribute of the returned function avg. Each item in avg.__closure__ corresponds to a name in avg.__code__.co_freevars. These items are “cells”, and they have an attribute called cell_contents where the actual value can be found.

>>> avg.__code__.co_freevars

('series',)

>>> avg.__closure__

(<cell at 0x107a44f78: list object at 0x107a91a48>,)

>>> avg.__closure__[0].cell_contents

[10, 11, 12]

7.6 The nonlocal Declaration

之前的 make_averager 实现不够 efficient,一个新的写法是:

# Wrong!

def make_averager():

count = 0

total = 0

def averager(new_value):

count += 1

total += new_value

return total / count

return averager

但是运行时出错:

>>> avg = make_averager()

>>> avg(10)

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

UnboundLocalError: local variable 'count' referenced before assignment

原因是:

- 在 closure 范围内,nested function body 内部对 free variable

foo的 “rebind” 操作,都会 implicitly create local variblefoo- 之前的

series.append(new_value)操作不会触发 “创建 local varibleseries” 是因为:list是 mutable 的list.append()的操作不会创建新的list

- 而这里

count += 1和total += new_value的操作会创建两个 local variablecount和total是因为:- number 是 immutable 的

+=操作会创建新的 number

- 之前的

- 隐式创建的 local variable 会干扰你对 free varible 的引用 (编译器不知道你要用的具体是哪一个)

解决这个问题的方法是:用 nonlocal 声明。It lets you flag a variable as a free variable even when it is assigned a new value within the function.

# OK!

def make_averager():

count = 0

total = 0

def averager(new_value):

nonlocal count, total # key statement!

count += 1

total += new_value

return total / count

return averager

7.7 Decorators in the Standard Library

7.7.1 Memoization with functools.lru_cache

注意 decorator 可以多包一层,以达到可以带参初始化的目的。

我们先看原始的写法:

# 原始 decorator

def foo(func):

print('running foo')

return func

@foo

def baz():

print('running baz')

相当于 baz = foo(baz)。

带参的写法:

# 带参 decorator

def foo(msg):

def wrapper(func):

print(msg)

return func

return wrapper

@foo('running foo another way')

def baz():

print('running baz')

相当于 baz = foo(msg)(baz)。

functools.lru_cache 就是一个带参 decorator,它的作用是 to cache recent call results。它内部会维护一个 dict 来记录 <arg_list, result>,从而达到 cache 的作用。适用的场景比如:

- http request

- 递归

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize=128)

def fibonacci(n):

if n < 2:

return n

return fibonacci(n-2) + fibonacci(n-1)

7.7.2 Generic Functions with Single Dispatch

这个厉害了。书上的例子是 “格式输出 html 代码”,针对不同的类型的变量,有不同的输出策略。不用 OO,用 function 就可以实现 overloading.

from functools import singledispatch

from collections import abc

import numbers

import html

@singledispatch

def htmlize(obj):

content = html.escape(repr(obj))

return '<pre>{}</pre>'.format(content)

@htmlize.register(str)

def _(text):

content = html.escape(text).replace('\n', '<br>\n')

return '<p>{0}</p>'.format(content)

@htmlize.register(numbers.Integral)

def _(n):

return '<pre>{0} (0x{0:x})</pre>'.format(n)

@htmlize.register(tuple)

@htmlize.register(abc.MutableSequence)

def _(seq):

inner = '</li>\n<li>'.join(htmlize(item) for item in seq)

return '<ul>\n<li>' + inner + '</li>\n</ul>'

- 带

@singledispatch标记的 function 我们称为 generic function.- 默认实现是

htmlize(obj) str类型的输入对应的实现是_(text)- 依此类推

- 默认实现是

- The name of the specialized functions is irrelevant;

_is a good choice to make this clear. - 可以映射多个输入类型到同一个 specialized function

需要注意的是:@singledispatch is not designed to bring Java-style method overloading to Python. The advantage of @singledispath is supporting modular extension: each module can register a specialized function for each type it supports.

7.8 Stacked Decorators

@d1

@d2

def foo():

pass

等同于 foo = d1(d2(foo)),注意顺序

Digress: @functools.wrap

decorator 有个小弊端是:decorated function 的 name 和 docstring 属性会跑到 wrapper function 那里去,比如:

def foo(func):

def func_wrapper(*args, **kwds):

"""This is foo.func_wrapper()"""

return func(*args, **kwds)

return func_wrapper

@foo

def baz():

"""This is baz()"""

>>> baz.__name__

'func_wrapper'

>>> baz.__doc__

'This is foo.func_wrapper()'

为了解决这个问题,我们可以用 @functools.wrap 来 decorate 这个 wrapper:

from functools import wraps

def foo(func):

@wraps(func)

def func_wrapper(*args, **kwds):

"""This is foo.func_wrapper()"""

return func(*args, **kwds)

return func_wrapper

@foo

def baz():

"""This is baz()"""

>>> baz.__name__

'baz'

>>> baz.__doc__

'This is baz()'

它的逻辑是:

wrap(func)返回一个functools.partial(functools.update_wrapper, wrapped=func)wrap(func)(func_wrapper)相当于func_wrapper = functools.update_wrapper(wrapper=func_wrapper, wrapped=func)

Chapter 8 - Object References, Mutability, and Recycling

We start the chapter by presenting a metaphor for variables in Python: variables are labels, not boxes.

8.1 Variables Are Not Boxes

Better to say: “Variable s is assigned to the seesaw,” but never “The seesaw is assigned to variable s.” With reference variables, it makes much more sense to say that the variable is assigned to an object, and not the other way around. After all, the object is created before the assignment.

To understand an assignment in Python, always read the righthand side first: that’s where the object is created or retrieved. After that, the variable on the left is bound to the object, like a label stuck to it. Just forget about the boxes.

8.2 Identity, Equality, and Aliases

Every object has

- an identity

- comparable using

is

- comparable using

- a type

- a value (the data it holds)

- comparable using

==(python 的foo == bar相当于 java 的foo.equals(bar))

- comparable using

An object’s identity never changes once it has been created; you may think of it as the object’s address in memory. The is operator compares the identity of two objects; the id() function returns an integer representing its identity.

The real meaning of an object’s ID is implementation-dependent. In CPython, id() returns the memory address of the object, but it may be something else in another Python interpreter. The key point is that the ID is guaranteed to be a unique numeric label, and it will never change during the life of the object.

In practice, we rarely use the id() function while programming. Identity checks are most often done with the is operator, and not by comparing IDs.

8.2.1 Choosing Between == and is

The == operator compares the values of objects, while is compares their identities.

However, if you are comparing a variable to a singleton, then it makes sense to use is. E.g. if x is None.

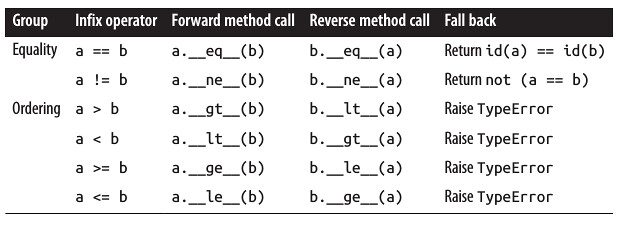

The is operator is faster than ==, because it cannot be overloaded, so Python does not have to find and invoke special methods to evaluate it, and computing is as simplecomparing two integer IDs. In contrast, a == b is syntactic sugar for a.__eq__(b). The __eq__ method inherited from object compares object IDs, so it produces the same result as is. But most built-in types override __eq__ with more meaningful implementations that actually take into account the values of the object attributes.

8.2.2 The Relative Immutability of Tuples

注意 immutable 的含义是本身的 value 不可变:

>>> a = (1,2)

>>> a[0] = 11

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

>>> b = "hello"

>>> b[0] = "w"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

你需要新的值就自己去创建一个新的,不可能把我当前的值修改一下再拿去用。

但是,Tuples, like most Python collections–lists, dicts, sets, etc.–hold references to objects. If the referenced items are mutable, they may change even if the tuple itself does not.

>>> t1 = (1, 2, [30, 40])

>>> id(t1[-1])

4302515784

>>> t1[-1].append(99)

>>> t1

(1, 2, [30, 40, 99])

>>> id(t1[-1])

4302515784

所以我们可以更新下 immutable 的定义:本身的 value 不可变;如果 value 内部包含 reference,这个 reference 不可变,但 reference 对应的 object 可变。

tuple 设计成 immutable 的好处是:

- python 中必须 immutable 才能 hashable,所以 tuple 可以做 dict 的 key (list 就不可以)

- function 接收参数 tuple 时不用担心 tuple 被篡改,可以免去 defensive copy 的操作,算得上是一种 optimization

8.3 Copies Are Shallow by Default

For mutable sequences, there are 2 ways of copying:

- By constructor:

a = [1,2]; b = list(a) - By slicing:

a = [1,2]; b = a[:]

N.B. for a tuple t, neither t[:] nor tuple(t) makes a copy, but returns a reference to the same object. The same behavior can be observed with instances of str, bytes, and frozenset.

但是!这样的 copy 都是 shallow copy。考虑 list 内还有 list 和 tuple 的场景:

a = [1, [22, 33, 44], (7, 8, 9)]

b = list(a)

a.append(100) # changes ONLY a

a[1].remove(44) # changes BOTH a and b

print('a:', a) # a: [1, [22, 33], (7, 8, 9), 100]

print('b:', b) # b: [1, [22, 33], (7, 8, 9)]

b[1] += [55, 66] # changes BOTH a and b

b[2] += (10, 11) # changes ONLY b because tuples are immutable

print('a:', a) # a: [1, [22, 33, 55, 66], (7, 8, 9), 100]

print('b:', b) # b: [1, [22, 33, 55, 66], (7, 8, 9, 10, 11)]

8.3.1 Deep and Shallow Copies of Arbitrary Objects

from copy import copy, deepcopy

a = [1, [22, 33, 44], (7, 8, 9)]

b = copy(a) # shallow copy

c = deepcopy(a) # as name sugguests

>>> id(a[1])

140001961723656

>>> id(b[1])

140001961723656

>>> id(c[1])

140001961723592

Note that making deep copies is not a simple matter in the general case.

- Objects may have cyclic references that would cause a naive algorithm to enter an infinite loop.

- The

deepcopyfunction remembers the objects already copied to handle cyclic references gracefully.

- The

- Also, a deep copy may be too deep in some cases. For example, objects may refer external resources or singletons that should not be copied.

- You can control the behavior of both

copyanddeepcopyby implementing the__copy__()and__deepcopy__()special methods

- You can control the behavior of both

8.4 Function Parameters as References

The only mode of parameter passing in Python is call by sharing. That is the same mode used in most OO languages, including Ruby, SmallTalk, and Java (this applies to Java reference types; primitive types use call by value). Call by sharing means that each formal parameter of the function gets a copy of each reference in the arguments. In other words, the parameters inside the function become aliases of the actual arguments.

The result of this scheme is that a function may change any mutable object passed as a parameter, but it cannot change the identity of those objects.

8.4.1 Mutable Types as Parameter Defaults: Bad Idea

这个现象前所未见!先上例子

class HauntedBus:

"""A bus model haunted by ghost passengers"""

def __init__(self, passengers=[]): # Tricky Here!

self.passengers = passengers

def pick(self, name):

self.passengers.append(name)

def drop(self, name):

self.passengers.remove(name)

>>> bus1 = HauntedBus()

>>> bus1.pick('Alice')

>>> bus2 = HauntedBus()

>>> bus2.passengers

['Alice']

>>> bus2.pick('Bob')

>>> bus1.passengers

['Alice', 'Bob']

The problem is that each default value is eval‐ uated when the function is defined–i.e., usually when the module is loaded–and the default values become attributes of the function object. So if a default value is a mutable object, and you change it, the change will affect every future call of the function.

所以,默认参数的逻辑相当于:

HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__ = []

bus1 = HauntedBus(HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__)

# bus1.passengers = HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__ (==[])

bus1.pick('Alice')

# bus1.passengers.append('Alice')

# ALSO changes HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__

bus2 = HauntedBus(HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__)

# bus2.passengers = HauntedBus.__init__.__defaults__ (==['Alice'])

The issue with mutable defaults explains why None is often used as the default value for parameters that may receive mutable values. Best practice:

class Bus:

def __init__(self, passengers=None):

if passengers is None:

self.passengers = []

else:

self.passengers = list(passenger) # or deep copy if necessary

8.4.2 Defensive Programming with Mutable Parameters

When you are coding a function that receives a mutable parameter, you should carefully consider whether the caller expects the argument passed to be changed.

8.5 del and Garbage Collection

The del statement deletes names, not objects. An object may be garbage collected as result of a del command, but only if the variable deleted holds the last reference to the object, or if the object becomes unreachable. Rebinding a variable may also cause the number of references to an object to reach zero, causing its destruction.

N.B. __del__ is invoked by the Python interpreter when the instance is about to be destroyed to give it a chance to release external resources. You will seldom need to implement __del__ in your own code. (感觉和 java 里面你不需要去写 finalize() 差不多)

- In CPython, the primary algorithm for garbage collection is reference counting. As soon as that refcount reaches 0, the object is immediately destroyed: CPython calls the

__del__method on the object (if defined) and then frees the memory allocated to the object. - In CPython 2.0, a generational garbage collection algorithm was added to detect groups of objects involved in reference cycles–which may be unreachable even with outstand‐ ing references to them, when all the mutual references are contained within the group.

To demonstrate the end of an object’s life, the following example uses weakref.finalize to register a callback function to be called when an object is destroyed.

>>> import weakref

>>> s1 = {1, 2, 3}

>>> s2 = s1

>>> def bye():

... print('Gone with the wind...')

...

>>> ender = weakref.finalize(s1, bye)

>>> ender.alive

True

>>> del s1

>>> ender.alive

True

>>> s2 = 'spam'

Gone with the wind...

>>> ender.alive

False

8.6 Weak References

概念可以参考 Understanding Weak References.

Weak references to an object do not increase its reference count. The object that is the target of a reference is called the referent. Therefore, we say that a weak reference does not prevent the referent from being garbage collected.

8.6.1 The WeakValueDictionary Skit

The class WeakValueDictionary implements a mutable mapping where the values are weak references to objects. When a referent is garbage collected elsewhere in the program, the corresponding key is automatically removed from WeakValueDictionary. This is commonly used for caching.

8.6.2 Limitations of Weak References

Not every Python object may be the referent of a weak reference.

- Basic list and dict instances may not be referents, but a plain subclass of either can solve this problem easily.

intand tuple instances cannot be referents of weak references, even if subclasses of those types are created.

Most of these limitations are implementation details of CPython that may not applyother Python iterpreters.

8.7 Tricks Python Plays with Immutables

The sharing of string literals is an optimization technique called interning. CPython uses the same technique with small integers to avoid unnecessary duplication of “popular” numbers like 0, –1, and 42. Note that CPython does not intern all strings or integers, and the criteria it uses to do so is an undocumented implementation detail.

Chapter 9 - A Pythonic Object

9.1 Object Representations

__repr__(): returns a string representing the object as the developer wants to see it.__str__(): returns a string representing the object as the user wants to see it.__byte__(): called bybyte()to get the object represented as a byte sequence__format__(): called byforamt()orstr.format()to get string displays using special formatting codes

9.2 Vector Class Redux

没啥特别的,注意写法:

class Vector2d:

typecode = 'd'

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = float(x)

self.y = float(y)

def __iter__(self):

return (i for i in (self.x, self.y))

def __repr__(self):

class_name = type(self).__name__ # 考虑到继承;灵活获取 class name 而不是写死

return '{}({!r}, {!r})'.format(class_name, *self)

def __str__(self):

return str(tuple(self))

def __bytes__(self):

return (bytes([ord(self.typecode)]) + bytes(array(self.typecode, self)))

def __eq__(self, other):

return tuple(self) == tuple(other)

def __abs__(self):

return math.hypot(self.x, self.y)

def __bool__(self):

return bool(abs(self))

*self展开这个写法帅气~- 注意

*foo要求foo是个 iterable (上面有__iter__()所以满足条件) __iter__()要求返回一个 iterator,上面例子里返回的是一个 generator (from a generator expression)- 注意它不是 tuple-comp,因为 python 不存在 tuple-comp 这种东西

- 然后根据 Iterables vs. Iterators vs. Generators 我们得知 a generator is always a iterator,所以这个

__iter__()写法成立 - 还有一种写法也可以:

yield self.x; yield.self.y

9.3 classmethod vs staticmethod

先上例子:

class Demo:

@classmethod

def class_method(*args):

return args

@staticmethod

def static_method(*args):

return args

>>> Demo.class_method()

(<class __main__.Demo at 0x7f206749d6d0>,)

>>> Demo.class_method('Foo')

(<class __main__.Demo at 0x7f206749d6d0>, 'Foo')

>>> Demo.static_method()

()

>>> Demo.static_method('Foo')

('Foo',)

@staticmethod好理解@classmethod第一个参数必定是 class 本身- 注意这里 “class 本身” 指的是

Demo而不是Demo.__class__ - 所以类似成员 method 第一个参数默认写

self一样,@classmethod第一个参数默认写clsdef member_method(self, *args)def class_method(cls, *args)

- 这个

cls可以当 constructor 用

- 注意这里 “class 本身” 指的是

class Demo:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

@classmethod

def class_method(cls, value):

return cls(value)

d = Demo.class_method(2)

print(d.value) # Output: 2

9.4 Making It Hashable

To make Vector2d hashable, we must

- Implement

__hash__()__eq__()is also required then

- Make it immutable

To make Vector2d, we can only expose the getters, like

class Vector2d:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.__x = float(x)

self.__y = float(y)

@property

def x(self):

return self.__x

@property

def y(self):

return self.__y

v = Vector2d(3, 4)

print(v.x) # accessible

# v.x = 7 # forbidden!

9.4.1 Digress: @property / __getattribute__() / __get__()

要想搞清楚 @property 的工作原理,我们需要先搞清楚 b.x 这样一个访问 object 字段的表达式是如何被解析的:

b.x$\Rightarrow$b.__getattribute__('x')- CASE 1:

b.__dict__['x']has defined__get__()$\Rightarrow$b.__dict__['x'].__get__(b, type(b))- 若是访问 static member

B.x则会变成B.__dict__['x'].__get__(None, B)

- 若是访问 static member

- CASE 2:

b.__dict__['x']has not defined__get__()$\Rightarrow$ just returnb.__dict__['x']- 若是访问 static member

B.x则会变成B.__dict__['x']

- 若是访问 static member

- CASE 1:

如果没有用 @property,一般的 b.x 都是 CASE 2,因为一般的 int、string 这些基础类型都没有实现 __get__();用了 @property 的话,就是强行转成了 CASE 1,因为 property(x) 返回的是一个 property 对象,它是自带 __get__ 方法的。

N.B. 我们称实现了以下三个方法的类型为 descriptor

__get__(self, obj, type=None) --> value__set__(self, obj, value) --> None__delete__(self, obj) --> None

@property 类型是 descriptor.

我们来看一下代码分解:

class B:

@property

def x(self):

return self.__x

# ----- Is Equivalent To ----- #

property_x = property(fget=x)

x = __dict__['x'] = property_x

然后就有

b.x- $\Rightarrow$

b.__dict__['x'].__get__(b, type(b))- $\Rightarrow$

property_x.__get__(b, type(b))- $\Rightarrow$

property_x.fget(b)- $\Rightarrow$ 实际调用原始的

x(b)方法 (TMD 又绕回去了) - 注意:此时

b.x()方法是调用不到的,因为b.x被优先解析了;这里property_x内部还能调用x(b)是因为它保存了这个原始的def x(self)方法

- $\Rightarrow$ 实际调用原始的

- $\Rightarrow$

- $\Rightarrow$

- $\Rightarrow$

这里最 confusing 的地方在于:b.x 从一个 method 变成了一个 property 对象,而且屏蔽掉了对 b.x() 方法的访问。一个不那么 confusing 的写法是:

class B:

def get_x(self):

return self.__x

x = property(fget=get_x, fset=None, fdel=None, "Docstring here")

9.4.2 Digress Further: x.setter / x.deleter

代码分解:

# python 2 需要继承 `object` 才是 new-style class

# python 3 默认是 new-style class,继不继承 `object` 无所谓

# `x.setter` 和 `x.deleter` 需要在 new-style class 内才能正常工作

class B(object):

def __init__(self):

self._x = None

@property

def x(self): # method-1

"""I'm the 'x' property."""

return self._x

@x.setter

def x(self, value): # method-2

self._x = value

@x.deleter

def x(self): # method-3

del self._x

# ----- Is Equivalent To ----- #

x = property(fget=x) # 屏蔽了对 method-1 的访问

x = x.setter(x) # 屏蔽了对 method-2 的访问

# 实际是返回了原来 property 的 copy,并设置了 `fset`

# x = property(fget=x.fget, fset=x)

x = x.deleter(x) # 屏蔽了对 method-3 的访问

# 实际是返回了原来 property 的 copy,并设置了 `fdel`

# x = property(fget=x.fget, fset=x.fset, fdel=x)

不那么 confusing 的写法:

class B(object):

def __init__(self):

self._x = None

def get_x(self):

return self._xshiyong

def set_x(self, value):

self._x = value

def del_x(self):

del self._x

x = property(fset=get_x, fset=set_x, fdel=del_x, "Docstring here")

9.4.3 __hash__()

The __hash__ special method documentation suggests using the bitwise XOR operator (^) to mix the hashes of the components.

class Vector2d:

def __eq__(self, other):

return tuple(self) == tuple(other)

def __hash__(self):

return hash(self.x) ^ hash(self.y)

9.5 “Private” and “Protected”

To prevent accidental overwritting of a private attribute of a class, python would store __bar attribute of class Foo in Foo.__dict__ as _Foo__bar. This language feature is called name mangling.

Name mangling is about safety, not security: it’s designed to prevent accidental access and not intentional wrongdoing.

name mangling 不会处理 __foo__ 这样前后都有双下划线的 name.

The single underscore prefix, like _bar, has no special meaning to the Python interpreter when used in attribute names, but it’s a very strong convention among Python programmers that you should not access such attributes from outside the class.

补充:If you use a wildcard import (from pkg import *) to import all the names from the module, Python will not import names with a leading underscore (unless the module defines an __all__ list that overrides this behavior). 从这个角度来讲,wildcard import 应该慎用。

9.6 Saving Space with the __slots__ Class Attribute

By default, Python stores instance attributes in a per-instance dict named __dict__. Dictinaries have a significant memory overhead, especially when you are dealing with millions of instances with few attributes. The __slots__ class attribute can save a lot of memory, by letting the interpreter store the instance attributes in a tuple instead of a dict.

A __slots__ attribute inherited from a superclass has no effect. Python only takes into account slots attributes defined in each class individually.

class Vector2d: